You come from a musical family, but I’m not sure your story is well-known among your fans. How did your family get started playing music, how did you get started playing the dobro and how has coming from a musical family shaped your perspective on the world?

Well, there are some great musicians on both sides of my family. We got into Bluegrass after someone gave my dad a mandolin in the early 80’s. He and my Mom went to a couple of festivals and they liked the family environment. When I was about 3 years old my older brother Gabe started playing the fiddle. I remember dancing around while he and my dad and a few family friends would pick and sing. Whether it was live or on the stereo, there was always music playing in the house.

After giving the fiddle a try and a few years of piano lessons, my dad suggested I try the dobro. My twin brother Loren had taken up the bass and everyone but me seemed to be having fun picking and singing. I just wanted to have something to play so I could join in. The dobro was the only instrument left at that point.

So everyone already had an instrument picked out?

Yes, and banjo wasn’t allowed. So the dobro was it. My Dad taught me my first few tunes; Cripple Creek, Fireball Mail and Steel Guitar Rag. I didn’t have my own instrument for the first 8 or 9 months. So I took my brother’s guitar – he had a mini guitar from when he was younger – and we raised the nut to set it up as a lap slide guitar. I mowed lawns to work up the $15 to buy a Steven’s steel (laughs). They eventually signed me up for lessons with Mark Switzer. He was the only guy in LA giving dobro lessons then and I think he still is the only guy in town now.

As soon as I got home from my first lesson, i dug out this compilation video that Mark had put together for my dad of The Seldom Scene with Mike Auldridge playing Walk Don’t Run/House Of The Rising Sun and Jerry Douglas playing a couple of solo pieces including A New Day Medley. The last part of it was Strength in Numbers on Austin City Limits. As soon as I watched that video it was over. I was hooked. I’m sure I watched it every day for a year.

Take us back to when you were new to the instrument. What were some of the hurdles you faced when you were learning to play?

Well, I didn’t know much about music and I wasn’t interested in learning music theory. My ear was pretty good, so I thought I could just rely on that. I just wanted to learn to play licks and solos. It took a long time before I got past that mind set.

My siblings had been playing for years and had already developed into great musicians. I felt like I had a lot of catching up to do.

Nothing like that to give you motivation!

Exactly! I was more disciplined at practicing that first year than I’ve ever been. I would rush home from school and give myself 30 minutes to eat something and practice until dinner time, which gave me 3 to 3 ½ hours. If I could, I would practice some more until my parents went to bed. That was rare because I’d have to do some of my homework. That was everyday for at least 3 hours and up to 8 hours on the weekends.

I could be wrong, but I’m willing to bet you didn’t learn to play by using tabs.

Well, it was a combination of things. We had the Cindy Cashdollar DVD – her first dobro DVD – so I learned some things from that. My teacher Mark would tab out just about any solos that I wanted to learn. I would try to work them out by ear and refer to the tab when I got stuck. Eventually I didn’t need the tab.

So, were you setting goals for yourself along the way? Seems like you were highly motivated…

Yes. I had all sorts of goals. Daily, weekly, monthly and yearly goals. I didn’t always reach them with in time frame I gave myself, but I kept working towards them anyway. I felt like I had a long way to go to catch up to my brothers.

I’ve always been a big advocate of encouraging students to find people to play with but that it’s not easy. It’s like trying to find the right spouse. There’s a girl around every corner but I’m not sure I want to get married to her. On the other hand you really advance a lot quicker if you learn by playing with others, especially good musicians.

Totally! That was huge for me. I was pretty terrified of making mistakes. At the beginning I refused to take a solo. Even if we sat there for five minutes just playing the chords, they’d be telling me “take a solo” and wouldn’t stop until I played one. So right off the bat, I was learning by playing with other people. After a few months no one would play with me because I wanted to play all the time. (laughs)

So you started when you were 14 years old. How long was it before you started doing gigs with the Witcher Brothers?

9 months

9 months?

That’s when I started sitting in with my Dad’s band at their weekly pizza parlor gig in Simi Valley. After I sat in a few times I ended up filling in for my brother Gabe on a few shows. Around that same time I got my first call for a session. I didn’t know what the heck i was doing! (laughs) but I could fake my way around I-IV-V chords.

So all of that happened really fast. I guess we all go through this process of becoming your own man (or woman) on the instrument. You start out wanting to sound like your hero but you get to the point where you realize as hard as I might try I can’t be someone else and start learning to trust your own instincts. You must have gone through the process quicker than most.

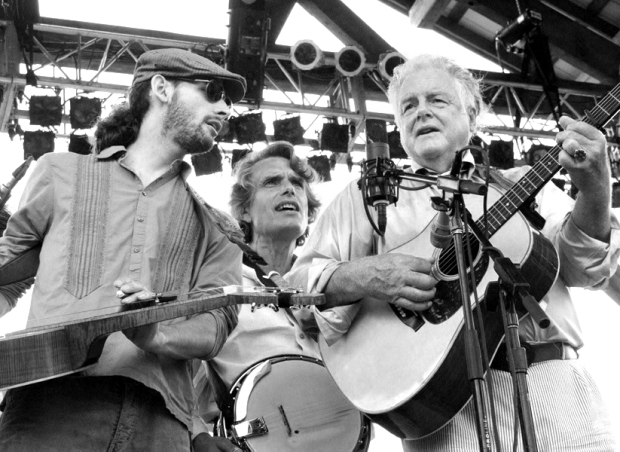

Tut Taylor recording sessions with Ronnie McCoury, Jerry Douglas, Russ Barenberg, Barry Bales & Fred Carpenter

I’m still going through that process! (laughs)

When did you get to the point where you felt like “those are my licks” This is my stuff ?

It’s been a number of years. But, I still feel like I’m just getting there right now. I’m getting more comfortable playing something the way I want it to sound instead of trying to recreate something I heard on a record. There’s still a lot I want to be able to do on this instrument that I haven’t quite figured out yet.

That’s such a valuable lesson. My wife is an actress so I wind up thinking about the similarities between acting and playing music. Anyway, I guess by analogy the dynamic would be like an actor trying to recreate the impact of someone else’s lines – trying to recreate someone else’s magic; but in a different time and place. No matter how much you study you can’t completely duplicate the internal process that led them to express themselves in their own unique way. “I could have been a contender” (quotes Marlo Brandon from the movie On The Waterfront).

Anyway, tell me more about that: getting into someone else’s head, their approach, etc

I really admire Jerry Douglas’ musicianship. I think the reason he is able to move between multiple genres and make it work is because of the level of musicianship he brings to the table.

I’ve always been interested in understanding a musician’s approach and how they think on their feet. I realized early on that there are a couple of different ways of approaching building a solo. One common approach is lick based improvising. You learn a bunch of licks and piece them together and play over chord progressions. That’s how I started. That’s not always the best way to serve the song. Instead, you could start with the melody; work the phrasing and add a few embellishments, maybe a lick or two. It seems like my favorite musicians utilize this approach. At this point, all I want to do is play the melody in the most beautiful way i possible can. It can be really challenging.

There’s a jazz saxophone player named Brian Kane with a website called www.jazzpath.com that I really like with applications for this. The short version is that after seeing scores of student’s complete programs in jazz studies he noticed that out of a graduating class maybe one or two students could improvise well. So he poses the obvious question: why is that? Why can’t most or all of the students improvise? Any his belief – and I think he’s right – is that the school of licks approach can work but it’s a really slow, tedious way to learn because it involves a lot of memorization and it takes most of us years and years to be able to digest that much information, synthesize it and generate our own ideas. Anyway, his approach is to get away from the school of licks approach and approach improvising with creative Intent and the use of stylistic inflections. For example one of the ways he does this is through an intervallic repetition exercise which restricts you to just four notes. The idea is learn to do a lot with just a few notes vs. doing very little with a lot of notes.

How do you approach teaching improvisation?

Sounds like I have a new exercise to practice. Thanks! I don’t consider myself a great improviser. As much as I love Jazz, I can’t hang in those jams. Some of my friends can play for 10 or 15 minutes straight without repeating an idea. I’m not there yet. I spend most of my time backing up singer/song writers. I find my self in situations live and in the studio where I’m playing songs I’ve never heard. Of course I improvise in those situations, but it’s based on the melody. I’m trying to do my best to serve the song. So, when I teach, I teach lick based and melody based improvising. We look at how we can take that melody and find its essence and find all the different ways that we can phrase it, look for embellishments, play the melody in different positions on the fingerboard and so on. When I first started playing I didn’t want to learn scales. Other than a technical exercise they seemed like a waste of time to me. As soon as i started figuring out melodies on my own, scales became my friend. I try to get people to learn the scales and immediately use them to find the melody. It’s pretty exciting when a student realizes they can find the melody in 5 or 6 places across the fretboard. Then we find the unique characteristics that each position has to offer. We talk about what makes a great solo. We use a basic formula for a decent structure that isn’t flat all the way across but has a peak somewhere…

Right! With a beginning, middle and an end!

Exactly! A solo that goes somewhere; takes the listener somewhere. And use that concept to connect these different places that we can play the melody to make something interesting. So that’s my basic approach – find it’s essence; edit out all the notes that you don’t need to play in the melody (which is really important in fiddle tunes.) Then find creative ways of communicating that melody and little ways of embellishing it.

I’m sure you’ve felt this, but once you get beyond the sheer mechanics it’s really easy to get into this territory where you start restricting and censoring your own ideas. So one of the exercises I’ve done with students is to challenge them to improvise for 2-3 minutes without stopping. Most folks find this incredibly difficult! They start censoring their own ideas almost instantly. Then you get into this Zen territory where the best ideas really come out of your unconscious where you’re not thinking about what you are playing.

Exactly! My favorite moments are when something completely unplanned pops up.

Let’s switch gears for a moment: You’ve played with a lot of great musicians over the years – Sara Watkins, Peter Rowan, Bette Midler, Dwight Yoakum, Dolly Parton, Missy Raines and the New Hip – what have been some of the highlights of those experiences and what have you learned along the way from your associations with other musicians.

Most of my heroes that I’ve had the opportunity to meet and play with have all been incredibly kind and supportive. The year I started playing I met Mike Aldridge, Josh Graves, Rob Ickes and Jerry Douglas. They all took the time to talk to me and encourage me. It was pretty amazing, with in the first month of starting to play I got a lesson from both Rob Ickes and Mike Aldridge when they came through town. I studied those tapes for years and learned every note they played!

I remember when Peter Rowan, Tony Rice and Mark Schatz came through L.A. I had played a few shows with Peter over the last year. I got to hang with them when they came through town. They got me up to play the whole second set of their LA show. It was ridiculous. I was 17 years old and had only been playing for 3 years! I played 3 or 4 shows with them. I still can’t believe that happened.

If that was me – 17 years old and playing with Peter Rowan and Tony Rice – well on the one hand it’d be really exciting but I’d be scared to death!

I was! But I jumped in there and tried my best to hang on. That’s what it’s like playing with Peter Rowan; it’s jump in and hold on! (laughs) Even if you rehearse it’s still unpredictable. The one time we made a set list we didn’t play any of the songs on the list. If you can survive that, you’re ready for just about anything.

Well I guess that’s one of nice things about bluegrass music is that it trains you to be ready for anything, since there’s no written music. I mean there’s no choreographer and a set of dancers. Whatever’s going to happen is going to happen; there’s a framework there, but there’s also a lot freedom.

Totally! Though I’ve played with plenty of artists who play the same exact solos every night and expect the show to sound just like the record.

Another really cool experience from when I was a teenager – I got a phone call one morning. I was still half asleep and this voice says “Michael? It’s Flux.” We chatted for a while and it turned out he had a gig playing with Dolly Parton in L.A. that he couldn’t make and wanted to know if I could do it. That was the coolest call. I was 18 or 19.

There’s a guy I know – Brian Nelligan – that had a similar experience. Do you know Brian?

Yeah, we talked about it. He played Letterman with Dolly. I think Brian told me that he actually hung up on Jerry when he got that phone call! He thought he was pulling his leg and hung up on him, then thought about it and had to call him back a few minutes later! (laughs)

You are both a musician and a photographer. Do you see any analogies or parallels between the learning process in becoming a musician and photographer? I just wound up buying my first semi-pro DSLR but I am brand new to photography and I’m taking a lot of bad pictures!

I really approach them both the same way. There’s a technical side and a creative side to each. I went to school for photography and it was all about learning how the camera works, how light works. Once you learn how it works the fun part starts. It’s all about experimenting to get different looks and trying to mimic different styles. It’s kind of the same process with dobro. There are a few photographers whose work I really admire and have tried to emulate. I always fail miserably but I usually learn something in process. (laughs). In music I try to emulate my hero’s but I end up failing and hopefully learn something in process. What kind of camera did you buy?

A Canon 7D

Nice. That’s the same camera I have. It’s an amazing camera.

I think it’s a great camera, but I don’t know how to use it. I’m sure there are folks out there who might listen to you play on your Clinesmith and think “wow, that guitar sounds great. If I had that guitar I’m going to sound just like that.” So to quote Lance Armstrong ‘it’s not about the bike.’ How do you think about the instrument and the sound of the instrument vs. the sound you can get out of the instrument and what advice do you have for someone who wants to make the leap from a starter instrument and move up to a professional quality instrument

There are a lot of great starter instruments out there. If the Gold Tone PBS guitars were around when I first started, I probably wouldn’t have gone through so many guitars before I bought my first Scheerhorn. I started out on a Regal import. I mowed lawns and washed cars; saved up all my money for that Regal. I played that guitar for about a year and eventually upgraded instruments a few times until I got a Scheerhorn. I struggled with getting a tone that I liked on the Regal. I was way into Mike Auldridge early on so I really like a nice, rich tone. I can see the effects of trying to make that Regal sound good in my technique today. It definitely shaped the way I put my hands on the guitar.

That’s such a great insight Mike. Over the years I’ve been asked countless times for advice on this or that instrument. Let’s put it this way – I love my Scheerhorn’s but I’ve played other guitars that I love too, you know… it doesn’t really matter to me what the brand is but it’s more about does the instrument give you the sound that you’re looking for? How do you think about this sort of thing?

I agree! I got my first Scheerhorn in 1998. I got it because that was the guitar that my hero’s were playing. I’ve played a lot of great guitars over the years…I don’t think one wood is best, one builder is best, one body style is best and so on. I think it’s a big combination. I have this sound in mind and I don’t care who made the instrument or what the parts are as long as it makes that sound. I eventually ordered an L Body Scheerhorn around 2002 or 2003. I loved that guitar. But, I felt like I was always wrestling with it to get what I wanted out of it. In 2008 Todd Clinesmith built me a beautiful Koa guitar. I played that guitar almost exclusively for 6 years. It totally changed my playing. I didn’t wrestle with that guitar. It gave me exactly what I wanted. Especially on the high string. It really sings! In 2014 I got my hands on a BlackBeard, one of the Jerry Douglas Signature Series Guitars made by Paul Beard. I’ve been playing this guitar almost exclusively for a little over a year now. I really love it. It’s top string really sings too. It has a huge sound but isn’t muddy in the mid range and low-end like most large body guitars. It doesn’t compete for space with a dreadnought acoustic guitar. It’s rich and beautiful and it cuts through. I’ve never heard or played anything like it.

Are there other builders that you admire?

There are so many great builders these days. Of course Beard and Scheerhorn make amazing instruments. I’m also really interested in Kent Schoonover’s guitars. I’d really like to own a Schoonover someday.

I played Jimmy Heffernan’s Schoonover a few years ago; a rosewood/spruce guitar. He handed it to me – I had no idea what kind of guitar it was – and I played it and thought – wow, this is a great guitar!

Kent is doing great work. His son Kyle is a great player and built an all mahogany guitar which is one the best guitars I’ve ever played.

I’m really glad to hear you say that. I’ve talked with Kent several times and I am so impressed with him and his guitars.

He’s really a great guy!

Yes he is. I want to thank you for turning me on to his modular spiders. Let’s talk a little bit about your live performance rig:

Up until the Aura system I hated plugging in. I’ve had the McIntyre, Feather and other pickups that have come along in the last 10-15 years and I absolutely despised them and avoided them whenever I could. Now I use the Aura pedal along with the Nashville series pickup and it’s amazing. Sometimes I even prefer to plug-in over using a microphone depending on the situation with the sound guy. I’ve gone through three generations of that pickup. The first two pickups (very early versions) went dead on me. Fishman was really great about overnighting replacements. The third time around I had Kent Schoonover install the pickup with his modular spider and the guitar sounded better, much better. The pickup sounds great. It’s been many years now and the pickup still sounds wonderful.

Did the pickup affect the acoustic sound of your instrument?

Yes, the early ones did. But I liked it .

Really?

It actually helped the sound of the Clinesmith. It’s been so long I’m not sure I can accurately describe what it did. I think it helped the sustain and controlled some of the harmonic overtones. I’ve also had so many different spider set-ups since I’ve changed from non-pickup to pickup and each one of those sounded different, but I’ve found that Kent’s modular spider sounds the best.

Sara Watkins recording session with Dave Sinco, John Paul Jones, Sean & Sara Watkins, Mark Schatz and Ronnie McCoury

Let’s talk a little bit about your instructional materials. Over the years you’ve taught lessons the “old-fashioned” way – in face to face settings in private lessons, at group settings at Kaufman Kamp, etc, but you’ve also published a couple of books and have put together a comprehensive library of downloadable instructional videos on your website and through Peghead Nation. Can you tell us a little more about the range of instructional materials that you have available? I’m also curious to know how your experiences in teaching in a live setting has influenced your approach to creating instructional videos?

I love teaching. From the raw beginner to advanced players. I love helping people find their voice on the instrument. A lot of times, people have bits and pieces and they just need help connecting them. It’s really fun to facilitate and watch it all come together. I’m a stickler for technique. That sort of stuff transfers really well from in person lessons to Skype lessons. I can move the camera and show full screen close-ups. It’s pretty amazing. It took a while for me to get used to teaching over the internet. It’s been 6 years and it’s going stronger than ever. My skype students are quite succesful too. It’s been really fun watching a handful of my students become professionals and the ones who are already professionals reach new levels! But, the most rewarding is watching people with no or little prior musical experience become musicians.

The downloadable lessons on my site cover the foundations for good technique. The songs give opportunities to apply that technique. Peghead Nation is really an extension of what’s available on my site and in my books. We lay a good technical foundation, but we also dive into understanding the fretboard and how to use some basic music theory concepts. Instead of just telling you to practice scales and arpeggio shapes, we show how to use those shapes to learn a song and connect every new song back to those shapes. I try to show my thought process for connecting the scales, triads and chord shapes in different positions to find the melody. I don’t want to teach people one way to play a song. I want to teach them how to find the melody for themselves and actualize the music they hear in their heads. That’s my goal with the Peghead Nation lessons. New lessons get posted every month. I head over to their studio every two or three months to record new lessons. Students can message me with what they want to learn and I try to work it into the lesson plan. I’m really happy to be working with them!

For what it’s worth I think your arrangements are really great. One of the things that I like is that they are true to the melodies; they are accessible and challenging for a beginner/intermediate student but not too challenging!

Thanks!

When I was learning I looked at the same books you did. I remember trying to learn from one particular book and it seemed liked that person picked the most difficult possible way to play something. I remember spending hours looking at that book and trying to learn that style and thinking “what the heck?” I quickly figured out that I didn’t want to play like that. So on a personal level I could relate to your style better. It made sense to me. I think there are probably some folks that can find value in the “100 licks you need to know” approach – I’m not saying that those things are bad. However, what I’ve found to be the most effective as an instructor and as a student is learning to play the repertoire in the bluegrass idiom. You go to a jam session, you play those tunes. That’s how you learn. Of course, in addition to learning where the notes are there’s always the issue of style and just learning how to play in tune.

It’s amazing how much instructional material has become available over the last 6 or 7 years. I think we are entering a whole new era of dobro playing. The internet has changed everything.

This instrument is really technically difficult. It makes so many buzzes and rattles with all of this metal on metal. Most of the technique is about getting rid of unwanted sounds. It’s rare for someone to actually master the technique and stop focusing on it so they put everything they have into the music. There are only a handful of people who have accomplished that.

Right! The value of basic musicianship vs. focusing on a bunch of licks! I’ve had that same conversation with Ivan Rosenberg. He told me that he went through the same experience when he started all he wanted to do was play licks. I had the experience of taking a lesson from Sally Van Meter about 10-12 years ago. I started playing for her and she said “well I can see that you’re more than a weekend player. Why don’t you play the melody to Banks of the Ohio in the key of B?” So I start playing the tune and after a few bars she stops me and says “great, now play the melody.” So I play it again and she stops me and sings back to me what I was playing. It was pretty sobering. I was playing more licks than melody and in doing so I didn’t realize I was pulling the listener all over the map. (laughs!) So the best lessons that I’ve had didn’t involve learning where the notes were as much as they did gaining insights into my own playing and my own technique, more about understanding myself than anything else.

I’ve had similar experiences. In my case, most of those experiences came from playing music with my brother. We were playing a beautiful slow song. I started playing my solo and half way into it he stopped playing, looked at me and said “what are you doing?” I said “what are you talking about man?” He said “no, no. Listen to the song, Listen to the melody”. So eventually our little jam turned into an exercise in which I was only allowed to play on one string with two plucks for the entire solo. It was all about editing out all the B.S. and finding the essence of the melody. That was the most difficult exercise I’ve ever done and the most powerful.

That brings to mind when I was in graduate school I had to take a class in poetry and I remember reading some poems by Elizabeth Bishop and thinking “this is really simple stuff. I could write something like this.” Then I sat down and tried writing my own poetry and found out it wasn’t so easy. (laughs)

How has your style or perspective changed over the years? What excites you about playing the instruments these days? What are you working on?

Well, I’m not trying to sound like somebody else every time I pick up the instrument. There was a turning point when I started playing with Missy Raines & The New Hip. I had to start holding myself accountable for what was coming out of my instrument. We weren’t playing Bluegrass. I couldn’t fall back on my repertoire of bluegrass licks. That situation forced me to come up with my own ideas.

What continues to excite me about playing the dobro is its vocal quality. To me that’s the most unique quality the slide has to offer. When I play, I want to sound like a great singer. That’s why players like Jerry Douglas, Derek Trucks, The Campbell Brothers and Aubrey Ghent still interest me. The Sacred Steel tradition is all about that vocal sound.

Did you had a chance to see David Lindley play when you lived in Southern California?

Only a couple times, he’s another one of my all-time favorites. He’s not just a slide player, he’s an amazing musician and it’s his level of musicianship which makes him stand out on the instrument to me.

What does the future hold for you?

Well, I have a lot of irons in the fire. I’m not touring much this year. Mostly playing up and down the west coast and in the bay area with various artists. I’m continuing to build up a resource of instructional material on my site and with Peghead Nation. I just finished producing a project for my good friend Willy Tea Taylor. I expect to that one to be released in the near future. I had a great time working with a lot of talented people on that record. I’m looking forward to doing a lot more producing! I’m also working on a new trio project with mandolinist Dominick Leslie and guitarist Jordan Tice. We’re setting up a west coast tour for this fall. I’m still playing a few dates with Pete Rowan and also Keith Little & Little Band. There’s plenty more I’m not thinking of. I try to keep my calendar up to date on my site. That’s where I look when I need to know what’s coming up!