SJ: About ten years ago I was visiting Jimmy Heffernan at his home in New Jersey when he handed me a squareneck resonator guitar to play. As soon as I played it I looked up at him and said “this is a great guitar! Who made this?” Up until that point I had never heard of Schoonover Resophonic Guitars. What inspired you to start building your own instruments and what is the background story of Schoonover Resonator Guitars?

KS: The inspiration came quite early for me. My dad was a fiddle player and some of my earliest recollections were of him playing “Pop Goes the Weasel” and my older sister and I dancing a circle around him as he played. By the time I was ten years old he had me sitting down with his D-18 trying to learn to play rhythm for his fiddle. He loved Tommy Jackson, Chubby Wise and Scotty Stoneman. August of 1971 found the family camped in a big tent at Bill Grant’s Salt Creek Park Bluegrass Festival in Hugo, OK. I was 13 years old. It changed our lives. We slogged through the mud for five days catching the stage shows and the all-night jams. As a family, we continued to make the yearly trip to Hugo through the 1970s.

After returning home that first year, I started learning the banjo and my brother Craig (known by all as Bozo) started to learn the dobro. Hey, every dobro player has to have a nick-name right? Well, we didn’t have a Dobro at the time so Daddy put a nut extender on his D-18 to get him started. Soon after, he bought Bozo an OMI Dobro through the mail from Slim Ritchey in Dallas.

The fascination for lutherie came from yearning for one of those beautiful, powerful banjos I encountered at the Bluegrass festivals. The Hugo festival hosted instrument contests and I remember the prize for the banjo contest was this gorgeous hand-made Thomas Banjo. I was blown away by the banjo playing of Don Thomas and seeing these great banjos that he made really made a mark on me.

Back home, Bozo and I woodshedded with Daddy’s collection of Flatt and Scruggs. You know,

putting the LP on the turn table and slowing it down to 16 RPMs. I also had Earl’s 5-String Banjo Instruction book. It was there in the back of that book that I found some basic information on building a banjo. I remember thinking “we could build a banjo”!

I think at this point I should tell you a little about our family. We were the ones that, you know, if the water well pump quit we pulled it out and fixed it. If the truck engine was worn out, we overhauled it. If the house needed a roof……you get the picture. The music was a part of our lives just as much as our spirt of being self- sufficient. There were many talented craftspeople in our family and extended family. I think we were all inspired by each other. My dad was always tinkering with fiddles. He would bring home a fiddle, sometimes in pieces, and put it all back together. There was an old fiddle maker in Ardmore that he would visit when he had something special to show him and I went with him one time. I was really drawn to that level of craftsmanship. Well, I never built that banjo. We saved our money and went to see Don Thomas and I came home with the banjo that I play to this day. But receiving that custom banjo and knowing the sacrifice the whole family had made in order for me to have it and knowing the great person who made it inspired me to write a paper in high school of my desire to build instruments.

After High School, I went to work in a paper mill and I was spending my spare time with old Chevy trucks and hunting and fishing. Bozo came home one day with this Walnut R.Q. Jones Resophonic Guitar! He and Mom and Dad had made a few trips to Wanette, Oklahoma to see Rudy and ordered that guitar. I remember seeing some photos he snapped of Rudy’s shop. Rudy had this big ole bandsaw and workbenches with guitar bodies and parts in this old brick storefront building with this sign that read “R.Q. Jones Resonator Guitars, Worlds Finest”. I thought that was the coolest thing! While working in the oil patch in South Texas I managed to build a mandolin from scratch and I cannibalized a cheap import for the tuners and fretboard. It was really bad. My Dad had Roger Siminoff’s book on Building a Bluegrass Mandolin which I studied but paid no attention to in the building of that mandolin. After moving back home to Oklahoma, I set up a workshop where I satisfied my need to create by building furniture and repairing the pawn shop specials my Dad would bring to me. I also built a few mountain dulcimers. I really don’t know why. I didn’t care for them much but I thought it would be a good place to learn some of the basic construction methods that I had ignored on that first mandolin.

By the fall of 1992 I had just finished building an 18’ Cedar-Strip canoe. Bozo brought his R.Q. Jones over complaining about a buzz. We opened it up and discovered the buzz was a result of the glue joints failing on some of the support posts. We repaired it and put it back together. Bozo said to me “why don’t you build me a dobro”?

Gaven Largent playing his rosewood/cedar Schoonover Resonator Guitar

SJ: So what process did you go through to learn how to build guitars? What qualities were you most concerned with when you designed your first guitar?

KS: Well, that first reso was just a copy of the RQ Jones – more or less. In our neck of the woods the Jones was King! So, why not start there? I had a lot of Walnut lumber from trees I had cut down and milled with a chainsaw mill. I had Irving Sloan’s book on Classical Guitar construction to guide me in the basics. So that first guitar was Walnut. After completing it, I remember thinking….this is not the way to build an acoustic instrument. Every great guitar that I had ever encountered was light and responsive in my hands. Studying my brother’s OMI Dobro and his R.Q. Jones I found they were built to withstand very heavy loads from top to back. However, the body was not well equipped to counter the over 200 pounds of string tension from the tailpiece to the neck. This resulted in the soundwell or the cone ledge becoming egg-shaped. My brother’s R.Q. Jones, which I had just copied, was built like a bridge. You could drive a car over it! I thought it was interesting that the back was so heavily braced and seemed to be designed to support the resonator yet the top was flimsy and prone to deformation from the string tension. This deformation, I believed, would have a negative effect on the cone’s resonance and sustain.

I thought about this day and night. I couldn’t sleep. I wanted to build another reso but I had no desire to build it with what I saw as a poor structural design.

What quality was I most concerned with? Well, ultimately, if you are building a musical instrument it is going to be tone. There is a tone that you hear in your head. You know it when you hear it. You know when you don’t. But it is more than that. It is the sustain, the response, the projection, the attack, and the decay…. If it does not have a voice that speaks to you it is just a guitar-shaped piece of furniture. Having built only one reso at this point, I felt that a richer more guitar-like tone might be achieved by getting rid of all that lumber on the back and build the strength into the top. I understood the importance of providing the cone a solid platform on which it could resonate; I just did not want the back to support it. My first and foremost challenge in designing the Schoonover reso was this. And this is what kept me up all those nights. To create a structural member for the top that connected the neck block to the tail block to withstand the tension of the strings without deformation. I thought by building the strength into the top, I would be able to brace the back in a more traditional guitar-like manner and keep it free and responsive. So, my goal was great tone that was more than just the cone but I felt the path to that goal was structural change.

SJ: Has the design and construction of your guitars changed or evolved over the years? If so, in what ways?

KS: The basic design idea of the neck-to-tail top support with the free back has not changed although the materials and construction methods have evolved. The first Schoonover designed resos (#2 through #6) had the top support made from steam-bent 1/4″ x 3/4″ maple strips laminated into what I referred to as a “tennis racquet”. I started with a single Maple strip formed into a hoop and then wrapped that with 2 more laminations with a filler strip between them that resembled a handle. The handle end was mortised into the neck block. The rounded hoop end was connected to the tail block. I built elaborate fixtures to bend and clamp the steamed strips to shape. Then, when dry, I glued it all together and ran it through a thickness sander. It was crazy! I really enjoyed the process at the time, but it was very labor intensive. In an effort to reduce the labor in each guitar I began cutting the top supports out of Finnish Birch plywood as one-piece units. I found this to be an improvement both structurally and tonally.

I was really pleased with the guitars and they were selling. But, I noticed that the sound was not as focused as my brother’s R.Q. Jones, and it seemed that the back was being overpowered. I was bracing the back dead flat at the time and the body depth was consistent all around on the sides. So I started tapering the sides and bracing the back in a dome and that tightened up the back. My construction methods have evolved to suit my build style and the tools and machines that I have. Some of my construction methods may be somewhat unconventional. For instance, I don’t cut the holes in the top until the guitar is completely finished and buffed. I do the same with the tuner holes and neck attachment bolt holes. The neck is never attached to the body until it is ready to be set-up. It is properly fit to the body with the correct angle and flossed in but can’t be attached until I cut the holes in the top. I built only that R. Q. Jones body style until just last year when I added (after much prodding from my son, Kyle) an “L” body.

Jeff Partin playing his mahogany/spruce Schoonover Resonator guitar

SJ: Interesting! What are the actual size differences between the Jones body style and your newer L body guitars? How do they compare from a sound/volume/playability perspective?

KS: There is virtually no size difference. The new body is a modification of a Martin “D” and scaled down in some dimensions. It is just a sexier-looking body to me. The upper bout and shoulders are more rounded than the Jones body. The construction of them is identical. If I had to pick-out any difference in the sound I would probably say that the Jones body may emphasize the mid-range a bit more. No difference in the playability.

SJ: From a builder’s perspective, what are the most important design features of your guitars that go into creating great playability and responsiveness?

KS: I feel when the structural requirements of the design with the proper execution of each construction detail balances with a minimum amount of material, great things happen. I build great strength into the body by interconnecting all the key structural elements. The top support is bracketed into the sides; the back is free of posts and domed with braces that are tucked into the lining. The neck heel is full width and allows the use of 3 attachment bolts. The fingerboard extension is also bolted down from the inside with 4 machine bolts. It is a very solid unit. It is lightly built with regards to the amount of material, but very strong. These things when coupled with a proper set-up help to advance the player’s experience with regards to playability and responsiveness.

SJ: So your guitars have been an open bodied design from day one, correct? No soundwell?

KS: That is correct. I have never made a soundwell guitar. The only guitar I ever built that utilized posts was that first guitar.

SJ: What constitutes a good set up on a resonator guitar? How do you go about setting up your own guitars – what kinds of materials go into a good set up to get the best sound out of a resonator guitar?

KS: Whoa! Really? OK! Three words…… Every little thing. No…. Every minute thing!

The sound of any reso is only as good as its set-up. The finest tonewoods assembled into a reso with the most gifted hands, utilizing the best hardware and set-up by someone without a clear understanding of what works will be totally uninspiring. What is a good set-up? Well, it starts with a structurally sound guitar. When I am setting up a customer’s reso I first evaluate it. If there are issues with the cone ledge not being flat and true, I start there. I feel it is very important for the cone to rest on a perfectly flat shelf. A resonator that is forced to conform to a cone ledge that looks like a potato chip will not be ideal. I have found this to be an issue with resos that utilize posts and domed backs. With fluctuations in temperature and humidity, the back will either dome up (high humidity which can cause the posts’ glue joints to fail) or flatten out (low humidity which can cause the cone ledge to rise under each post). I have a platform that I mount to the top of the reso and route the cone ledge or soundwell flat and true again. The neck joint must be secure and at the proper angle.

For my own guitars, the cone ledge is created when I route the holes in the top. I use a specific setup for the route so all of my guitars have a consistent cone ledge depth. I cut the neck heel to provide a specific amount of relief at the nut when a straight edge is laid on the guitar top and on the neck shaft without the fretboard. This accounts for the tension of the strings so that when strung to pitch the neck will be on the same plane as the top of the body. I arch the spider and level the tips of the legs perfectly by manipulating it with a hammer and lapping it on a granite plate. The backside of the spider “hub” is machined to further lighten it. The bridge height is adjusted to maximize the available space under the coverplate’s palmrest. I also mount the Modular Bridge about 3 degrees off of perpendicular to the Modular Spider with the top of the bridge angled back toward the tailpiece. I use a spacer under the tailpiece if I want to moderate the down-pressure on the cone. One thing I have learned is how to calculate the maximum bridge height for a guitar. If I know the cone ledge depth and what cone and coverplate are used, I can solve for the bridge height. It takes the guesswork out of it. Cutting the string slots in the nut and saddle is where the Mojo is. You can have every other thing right, but if you don’t get this right there is no magic. It takes practice and an understanding of a string’s dynamics to have consistent success.

In terms of materials, the following are important:

- Bone nut: correct height, properly fitted, shaped and polished. I am an advocate of cutting string slots that give equal space between strings as opposed to string slots that are cut center to center. It looks right to my eye and I like the playability better.

- Cone: At one time it was only Quarterman. Now, I let the customer decide as long as it is a Quarterman, Scheerhorn, or Beard.

- Spider: Schoonover Modular Spider

- Bridge: Schoonover Modular Bridge Phenolic-capped Maple.

SJ: I’ve played a lot of different squareneck resonator guitars over the years and I’m sometimes puzzled at how two different builders can build a guitar with the same kinds of wood and yet those guitars may sound/play very differently. How do you view the intersection between the design of a guitar and the craftsmanship of the builder vs. the influence of tone woods used to build the guitar?

KS: I absolutely believe the differences between two luthier’s design and skill will outweigh any similarities one might expect to hear because of the use of the same wood species. You also have to understand that we tend to discuss different woods and harp on their generalities. You know, Maple is bright, Mahogany is sweet, and Brazilian Rosewood is…insert divine adjective here. In reality, there is a lot of variability in wood within species. There can be a lot of variability in wood from the same tree! Even the way the grain is oriented in the wood affects its stiffness and will therefore have to be considered in the construction for the way it can influence the sound.

SJ: On your website you list options for different tone woods – I’m curious to know which wood combinations are the most popular and what kind of process do you go through to help some select the tone woods for their guitar?

KS: Overall, the most popular wood for my guitars has been Maple. But, there have been cycles. There was a time it seemed Rosewood/Spruce was very popular. It’s funny, the first two guitars I built were Walnut and I didn’t build another Walnut guitar for over 20 years. I have built three in the last year!

Some customers know exactly what they want. Some don’t….I have to tell a story. A man called and made arrangements to meet me at my shop. He had seen one of my guitars and was excited to have a reso made. He drove from the Texas Panhandle, about a five hour trip, to spec out his guitar. I think we looked at every stick of wood I had. After hours of discussion and lunch and even a little pickin’ he says “I can’t decide between a Maple or Rosewood/ Spruce, I think I’ll just have to have one of each!” That was a fun day and I made a really great friend. I mostly do a lot of listening. I want to know what type music they play, and in what type of setting. Are they into tradition or more contemporary in their leanings? If it is a long distance customer I offer to email photos of particular sets of wood. Last year, I had a customer in Japan choose his wood from several sets of Claro Walnut using this method. If the customer has distinct desires regarding tone, without a clear choice in species, I make recommendations based on my experience. For instance, I had a customer who said he loved the look of Maple but he did not like that “bright, harsh sound”. I chose a set of outstanding Quilted Bigleaf Western Maple. Tonally, I have found this wood to be more like Mahogany than Maple.

SJ: What was the inspiration to design and create the Schoonover Modular Spider? It seems to me that your Modular Spider was a perfect solution for some of the issues associated with the installation of the Fishman Nashville Series Pickup, but I’m not sure which came first.

KS: You know the old expression – “necessity is the mother of invention” – in this case it was frustration. After building several guitars and all the various jigs a guitar builder tends to rely on and refining my methods of work, I had everything ironed out to suit me. Everything was a breeze until I went to set-up the spider-bridge inserts. I don’t know why I hated that so. I hated fiddling with those tiny bits of wood, pressing them into that ragged slot. I never felt good about that. Well, I had lots of spider bridges to fiddle with. I had visited with Bob Reed at his shop a few times back in 1993 and I was buying my spider bridges from him. After he passed, I approached his family about acquiring the match plate for the spider bridge which I did. This was the spider that Rudy had used in his guitars. So I began having these spiders cast and sold many of them through Beverly King and Country Heritage. Over the years I spent many hours experimenting with spiders by filing, drilling, grinding, resonance tuning and measuring deflection. I just thought there had to be some room for improvement. I noticed all of the different bridges available for banjos and how a bridge change could alter the tone and I thought how great it would be if I could change a bridge as easily as a banjo player does. So, I machined the bridge slot boss off flat on a spider and fashioned a few bridges of different materials. At first, these were two-piece bridges. I liked how they made the guitar sound and the fact that I could easily alter the tonal character of the reso. So I tooled-up (had to make more jigs) and had some custom cutters made and started machining the one-piece bridge stock in strips. I had a few of them in guitars when the Fishman Nashville Series Pickup hit the market. I had a customer order a guitar with the pickup so I ordered the Adjustable #14 for it. I installed that pickup and it worked out okay. But I thought how cool would it be if Fishman would install their pickup in my Modular Bridge. I called Fishman and explained what I had and asked if I could I send them a sample. They just said their production was setup and that I would just have to find a way to make it work. Little did they know my moto in life has been “Find a way or make one”. ☺

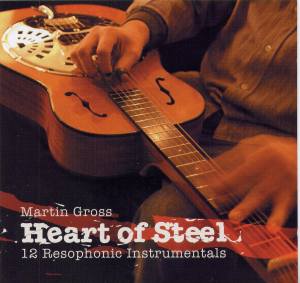

SJ: It’s got to be exciting that two of the hottest new players on the scene – Jeff Partin and Gaven Largent – are playing your guitars. How did you come to meet both of those fine players? I’m also curious to know what wood combinations they choose when they commissioned you to build them a guitar? Did they know what they wanted or did you guide them through that process as described earlier?

KS: It is really exciting for me to hear the music these guys make. That is what every luthier wants, I think. To have your instruments put to use at that level. Gaven tears it up! I mean, you should see his guitar! It looks so cool, like it’s 60 years old already! I received a phone call from a man in Florida about 2 years ago. He says “I saw one of your resos at a festival. It was a great sounding guitar.” He continued, “It looked like the thing had been in a house fire!” I said with a grin…..You must have run into Gaven Largent! Kyle was living in Nashville and met Gaven at Reso-Summit a few years back. Gaven bought a Rosewood/Cedar guitar that Kyle had on hand at the time. He has commissioned me to build him a new Flamed Maple guitar that is just now getting underway. He is excited. Though, probably no more than I!

I have to credit Kyle for getting a guitar into Jeff’s hands as well. I don’t get away much but Kyle is like the Schoonover Resophonic Guitars PR division. He contacted Jeff and told him about a Mahogany/Spruce with Snakewood trim I had built for a show that I did not make it to. Jeff jumped on it. He can really make that thing sound good. Jeff really knows what to play for the song. He is a very talented musician. I think that Mahogany/Spruce fits him nicely.

SJ: Can you give us a quick synopsis of the base price for your guitars, different options and current wait times?

KS: Sure. The base price is $3,300.00. That is for a Flamed Maple, Black Walnut or Genuine Mahogany guitar. Fully bound with black, tortoise, or ivoroid. No up-charge for shaded finish. Includes Premium Custom Case.

Options

- Wood Binding

- Various purfling schemes

- Custom Inlay

- Many available body woods

Current wait time is about 12 months.

SJ: How do you like the daily life of a luthier? Do you sort of revel in the smells and the sawdust and the chips and the band-aids? Any closing comments for our readers?

KS: Well, I love it! I love working with wood. I love the music. The people I have come into contact with have all been a blessing to me. Every single one. I am thankful to God for the opportunity to spend some of my days building resophonic guitars that are used to bring joy to the people who play them. And without the unwavering support of my wife Tammie, I would not be building instruments at all. I try to get to the shop every day and make something good happen. I have been able to meet some really top-shelf luthiers over the years and have aspired to be a luthier for so long; it sometimes startles me when I am called that. When I am called a luthier I am reminded of former Phillies first baseman John Kruk’s response after being called an athlete……”I’m not an athlete, I’m a baseball player!”