Originally published at http://www.robanderlik.com in 2009

SJ: When did you start playing dobro? What got you interested in dobro in the first place?

BC: I started in March of 98. There’s a little bit of a sob story leading up to this answer. I spent a lot of time playing while growing up doing recitals, jamming with friends, etc. I never really learned how to practice a lot and at the same time take care of myself physically. It really doesn’t work to play all day and not get any other kind of exercise, so eventually I hurt my wrists. I actually ended up having surgery on both wrists at the same time while on spring break one year. But this was after a several year hiatus of really being able to play and practice. So anyways, that whole period of my life was pretty interesting. That’s when I got into engineering and computers. Somewhere in the middle of that hiatus, I befriended Ronnie Simpkins who was playing bass for the Tony Rice Unit and The Virginia Squires. He invited me to come with him down to Richmond to hear the Squires play. On the way there, while sitting in traffic, he put in the Tony Rice recording Cold on the Shoulder. That was my first time really listening to dobro and Jerry Douglas. Within a day I had my own dobro. It was easier on my hands at the time and though I couldn’t play too much, I messed around with it for a few minutes here and there. In ’98 surgery worked wonders for my hands and I haven’t had any trouble since. I went to Merlefest that year, saw a Mike Auldridge workshop and asked him if he could teach me. I was so thrilled when he agreed to. He only lived 45 minutes from me. And that’s how I got started.

SJ: How did you learn to play dobro so well in such a short amount of time? What were the most valuable learning experiences for you in becoming a dobro player?

BC: Ah, well, thanks. I appreciate the compliment. The music I’ve been able to come up with has been the result of a lot of woodshedding, and carrying over things I had learned on previous instruments. I think it takes a long time to be able to play music freely, but to overcome the physical limitations of a new instrument isn’t nearly as difficult as just initially learning to be musical. I also feel like alot of what I’ve learned on the dobro has been thru small epiphanies brought on by battling what have been my perceived limitations of the instrument. I’m only now starting to embrace those limitations and see them as benefits. Also, thru studying with Debashish, I learned that there aren’t nearly as many boundaries as I once thought, and somehow that’s made everything feel more wide open. I’ve played a lot of different instruments over the years, but the longest stints have been on the instrument I started on, the piano, and the one I’m playing most now, the dobro. The former probably being the instrument allowing the most freedom for playing musical ideas and the latter being one of the least cooperative. It has been challenging to go from being able to play full lush chords with 10 fingers to being lucky to play some semblance of the same extended chord. Or to go from an instrument where any particular melody line can come out fairly instantaneously, and in tune (as much as a temper tuned piano can be in tune) and then to go to an instrument where it could literally take years or be close to impossible to phrase the same melody line. There’s been plenty of times where I’ve felt stifled and wondered “Why am I putting myself thru this”, but then I always come back to it…usually a few minutes later. So I figure having a lot of non-dobro music in my head, and being headstrong about finding a way to get it out on this instrument has helped me evolve my playing to where it is today.

My most valuable experiences…I feel like they come in such strange ways, some big and some small and fleeting. I had a small and unexpected one sitting on my couch by myself a few days ago. For some reason something just clicked and I’ll never see the instrument quite the same again. But more obviously, it’s been learning from my favorite players, both dobro players and otherwise. Mike got me off to a great start, but then I moved out of that area. I’d go down to Nashville to meet with Rob I and Randy K. I spent some time with Roger Williams in West Virginia at the Augusta Heritage Center and Sally Van Meter in my first or second year of playing. And I spent a few years studying with John D’earth from the UVA jazz department. He’s an amazing player and teacher. Also Billy Cooper taught me a lot about playing steel in a short amount of time. Anyone wanting to learn pedal steel should go see him. He’s got a great teaching method.

I went on the road playing dobro with the Larry Keel Experience after having played dobro for 2 years. That was a serious bluegrass crash course for me. I was trading tours with Curtis Burch, and when we’d be trading off on the crossover night we’d usually pick together on stage, so that was always a blast. Curtis is a really great player and knows all sorts of neat pockets around the neck of the instrument. We played the only live version of the tune Suitcase from the GDSessions one night at Green Acres in NC…that was really cool. Also, having Ivan as a roommate has been a really cool experience…he’s the best roommate ever 😉 I think we both taught each other a lot about what each of us needed to learn musically also. Our styles and approaches are complimentary in an almost yin yang sort of way that seems to work out just right. Actually, as I type this paragraph, I’m waiting to drive to the airport to pick him up so we can start recording our duet project.

Most recently, working with The Biscuit Burners has been very enlightening. And studying with Debashish has been essentially the pinnacle of my musical education. The disciple-guru relationship is really an amazing spiritual connection. I wish that sort of education was more prominent in the states.

SJ: How would you describe your style as a dobro player? Can you give us any insight into your tool box of techniques – slants, pulls, right-hand, etc, etc?

BC: When I got into dobro, I knew nothing about the history of the instrument. I only knew Mike and Jerry. I just assumed that was how everybody played (duh). There’s so many good guitar players or piano players or whatever…I just assumed there was thousands of killer dobro players. And as I said before, since I grew up playing piano, I just assumed I was supposed to be able to get all of that music out of the dobro. I didn’t know anything about the stage of development the instrument was currently in. That’s how it started for me and I didn’t learn any differently until I had already gotten a decent grasp on the instrument from a technical perspective. If I’d known better when I started, I may not play the way I do now, for better or worse. Also, trying to find a way to get all this stuff out has made some of the stuff that I do sound successfully sweet and unique, and also some of it can be kind of weird and just sort of unique in the kind of way that a person doesn’t necessarily want to be unique (did that make sense ;-). But it’s a learning process and I’m heading somewhere and am just constantly trying to refine what I think sounds good, being true to myself, and all the while respecting my heroes sounds as their own sounds. Style is probably the most important thing for me. As far as my techniques go…technique is what I really try to learn from my slide heroes. I try to learn how they get around the instrument and then apply those ideas to the music I want to play. I’m just trying to take whatever ideas I can, technically, that will break down the barriers that could hold me back from being able to smoothly play whatever I want.

SJ: What tunings do you use?

BC: Mostly just High bass G, standard bluegrass tuning and DADF#AD. I always figure there’s more music in any one tuning than I’m ever gonna get out of em anyways and it just seems like so much of a pain to retune a bunch during a show, although I see people successfully do it on guitar all the time. But, they don’t have a cone that moves around that throws everything off. I dunno, maybe I’m just lazy 😉 . Every now and again I’ll bring the 4th string up a whole step or the 2nd down a half or whole.

SJ: Why do they call you the king of the 6th and 8th frets?

BC: Ivan taunts me with that as a joke. I’m a digger, and that means a constant search, and sometimes it takes a little while to find ‘the sound’, and along the way, some strange noises might happen. And in G dobro land, the 6th and 8th frets typically embody strange noises (laughing).

I guess it stems from my studying jazz, but also just from the angle I approach music from. I really try to play just my thing. And I’m always searching for a new way to sound. I spend a lot of time woodshedding and sometimes the things I’m working don’t sound in any way traditional. I think it throws some people for a loop cause they are used to hearing the dobro sound differently than what I’m doing. But, really, I’m just trying to find a new way without touching too much of what my heroes have done. But don’t get me wrong, I still love to sit back at a festival and hear anybody, beginner or not, shed on their versions of Fireball Mail or something. I love the instrument and I’m not down on learning from and playing our dobro heroes ideas, but there’s a drive inside me to find a new way, and sometimes in the process that means sounding sort of weird for a while, hopefully just till things get ironed out…hence the 6th and 8th frets comment. I actually don’t play there very often unless I’m in Eflat, F, Em, C, Bb, Db or G. Well, I guess I do get around there from time to time. But, it’s not a goal for me to play weird music. I’ve actually written a lot of very trad sounding tunes in some different genres…Old Timey, Hawaiin, Bluegrass, Pretty dobro Acoustic Thingy’s, and Jazz

SJ: I was fascinated to hear that you had recently traveled to India to study with Debashish Bhattacharya. What did your studies consist of? What did you learn from the experience?

BC: My studies with Debashish began with the Ahiri Institute for Indian Classical Music in NYC. He was a guest teacher there, and I had been listening to his music for a while and jumped on the opportunity to study with him. As things turned out he is not only a great teacher but a really cool guy and we’ve become close friends. This past Nov/Dec was my first trip to India. My wife and I stayed in a small apartment in Calcutta within walking distance to Debashish’s house. Living in the city was really wild. Studying with Debashish was just amazing. He is an unbelievable musician. He was awarded the President of India award when he was 20 for his musicianship! His skills on slide guitar are nothing short of just unbelievable. To give you an idea, and not to insinuate that he plays just for the sake of technique (cause he can play a new melody line one after the other for who knows how long), but just as an example of what this guy can pull off if he wants…if you go up to the 24th fret of a dobro (mine has 24) and play a scale starting on that D note up to where the 36th fret would be…I’m talking way up in the coverplate region…I could say, okay Debashish, play for me 1, b9, b3, 4, 5, b6, #7 and 1, he could blaze thru it all perfectly in tune and with considerably more speed than most people can play hammer ons and pulloffs at the 1st and 2nd frets. It’s really pretty wild. So anyways, he’s teaching me a completely different way to play music on slide guitar than I’m used to. Oftentimes I’m concentrating on a single string and relying on the glissando to work thru the notes. In fact, when someone is really playing Indian Classical music properly, they play thru the notes, rather than use them as targets. Debashish has also been teaching me some ragas, traditional bandishes (tunes) based on those ragas, and how to unfold a presentation of an Indian Classical composition. Maybe most importantly though, he brings a very enlightened spiritual element into his music that I love and respect. For me, he’s like the wise teacher I’d see in a movie that always has a great analogy or parable or story for everything…he’s totally that guy! He helps me to learn to see beyond the technique and the instrument, into what the music is really about, something that I think it can be easy to lose in this fast paced world.

BC: What exactly is a chaturangui and how do you play it? Do you include it in your live performances? How did you get interested in this instrument in the first place?

BC: A Chaturangui is an instrument of Debashish’s creation. It is based on an old style of Veena. It’s kind of like what you’d get if you were to cross a sitar with a dobro. It’s got 22 strings. 6 of them are main melody strings, 4 are called chikari or drone strings which are similar in purpose to the 5th string on a banjo, and the rest are sympathetic. The sympathetic strings, when tuned properly, will ring in the background in accordance with the note being played…there’s some cool physics at work! It is played with similar accessories as a dobro, though the technique is a bit different. I am working on a song for Biscuit Burner record 3 (although it’ll kind of be record 4 cause were just finishing an electric record that came together in a strange serendipitous and unplanned sort of way). The song is going to be a melding of Appalachian style harmonies but with some Indian style inflections. I’m hoping to make it pretty natural sounding, and not too much like a Frankenstein…we’ll see. For me, falling in love with the Chaturangui was just natural. I’ve always really enjoyed, and sought out, music from all over the world, so when I heard this slide guitar from India I was blown away.

SJ: I’ve got to ask this question…what would Bill Monroe think if you included a chaturangui at a performance at a bluegrass festival? Is there a way to incorporate the technique and feel of music made on the chaturangui with the Biscuit Burners or in contemporary acoustic music in general?

BC: Well, it’s hard to say what Bill would think. I suppose he’d either be cool about it or think it has no place in ‘his’ music. I see the important part of tradition, with respect to music, as simply people getting together with others and making music happen. I think that’s the most important thing, more than who is playing what instrument and in what fashion. Of course not everybody might like the resulting sound, but it’s so much more gratifying for someone to follow their own voice than ‘trying’ to be a certain way…trying to write songs that say a certain thing. It seems like this can lead to a loss of individuality. Individuality has made all of our favorite music what it is. I love what we know as ‘traditional’ bluegrass, but the bands that I really love still followed their hearts and their sound no matter what. The list would be long, but one that stands out in my mind right now is The Seldom Scene. (Well, are they considered traditional? )

The Chaturangui is an amazingly expressive instrument. Anything can be played on it and with this big huge bed of sound behind the melody due to all the sympathetic and chikari strings. I think once people open their ears to it, they’ll realize that a folk song, blues song, Hawaiin song, New Acoustic song or whatever else can sound really really cool with one of these things. It allows a slide guitar player to create a sonic space never before possible, and it doesn’t just have to be Indian music any more than a guitar has to play rock and roll..

SJ: Tell us about your band – the Buscuit Burners – how did the band come together? Is fiery mountain music different than bluegrass?

BC: The Biscuit Burners actually started out as an all-ladies band. They were just going to play one show for an all ladies bluegrass and old time show. So many people play music here in Asheville that there was actually like 20 bands of mostly all women. All the gals had a great time playing together, but Shannon and Mary thought they’d like to take it a little farther. So I started helping them out a bit. Then we heard this new hot guitar picker moved to town and we tracked him down right away, and as it turned out he was the perfect guy for the job (Dan Bletz). What we call ‘fiery mountain music’ is different than bluegrass. We pull inspiration from a lot of the aspects of bluegrass, but also from other styles we’ve grown up listening to. We don’t normally play any songs from the traditional repetoire and our songs aren’t structured in the same way as a bluegrass song. We play almost exclusively original material and arrange it in ways influenced by New Acoustic, Pop, Classical, and whatever else. We try every idea we have and don’t ever think about how it fits into any sort of genre.

SJ: Can you comment about your approach to providing rhythmic support on dobro? What techniques – chops, chucks, rolls, etc – do you use with the Burners to provide rhythmic support?

BC: Well, recently our friend Jon Stickley started playing mandolin with us, so that has really changed my role in the band. But previously it was clawhammer banjo, guitar, bass and me. There were certain tunes and certain arrangements that would really allow the song to be completely filled out on it’s own accord, but there were others that we really struggled with to pull together the rhythmic presence that we wanted. Usually it came down to an arrangement decision and if that didn’t work, sometimes it would just flounder around until it dropped off the setlists entirely. The original 4 piece was very challenging for me, especially in a live setting, where the sound reinforcement could potentially be suspect. I would oftentimes feel a lot of pressure to fill in ‘space’ because there wouldn’t be too much of a rhythmic presence. The girls we’re just getting started on their instruments, though Dan was already a great picker. I figure I learned a lot about what to do, and what not to do. When I’m practicing with the band, I’ll set up a microphone and try a bunch of different combinations of any type of rhythmic support I can think of on the dobro, then just pick what seems to complement what everyone else is doing the best. But all that stuff you mentioned is fair game. There’s also a cool technique that Pete Reichwein taught me (thru the email) that uses the 4th finger for a back strum to get a bit more of a rhythm guitar type of sound. That’s really come in handy.

SJ: Tell us about your gear – what guitars do you own?

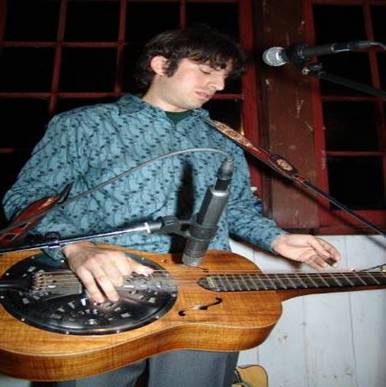

- 2001 Koa L-Body Scheerhorn

- 2005 Brazilian/Cedar Sheerhorn

- 2002 Electric Scheerhorn

- Bear Creek Weissenborn style guitar

- 1927 National Style 2 tri-cone

- Stelling Red Fox Banjo

SJ: Where did you find the wood for your new Scheerhorn resonator guitar? Why the combination of Brazilian rosewood and cedar?

BC: My buddy Brian Calhoun is part of a two-man team that builds Rockbridge guitars (http://www.rockbridgeguitar.com They are very very fine instruments!) Brian let me pick my favorite piece of Brazilian out of a few dozen sets he had. There were so many beautiful ones that it took me hours to decide. I’m not so sure it sounds any ‘better’ than Indian would sound (Tim Scheerhorn told me there’s a fairly distinct difference in tone, but of course quality is left to the listener). I just love the look of the Brazilian and the sound of rosewood. I love art and painting, etc. and to my eye, the Brazilian is more like a painting than most wood I’ve ever seen.

While down at Tim’s shop, we we’re discussing the top of the guitar and he tapped on a few different types of spruce and then cedar. I was amazed at the differences between them all. I knew the cedar was right for me. Our band (in the right sound environment) has a warmth to it due to Shannons soft voice and Dans rosewood guitar, so I thought the Cedar would be the best fit.

SJ: What does your live rig consist of? Any comments on getting good “live” sound?

BC: Ah, the live rig, it’s like a living entity unto itself, constantly changing. Right now I’m using an AER amp, a Neumann KM-84 mic and a Schertler pickup. I can blend the way I want on the amp and send a XLR DI out the back of the amp to the soundboard. I also have separate control over how much volume comes from the amp in case I need a little or a lot. It’s a nice sounding rig and allows me some crucial control over the mic / pickup blend.

SJ: What have been some of your favorite gigs playing with the Biscuit Burners?

BC: The best was playing with Vassar Clements at the Ryman. We miss Vassar dearly. His musical spirit was an honor to be around and a lesson for every musician. Of course the festivals are always a blast. It’s great crossing paths with all our musician friends and meeting more and more people. The more we travel around, the more great folks we meet, so touring becomes partly like visiting friends. We got a bus recently that makes touring so much nicer for us. We love doing the school programs and turning the kids on to how fun it can be to play music (even more fun than Playstation!). A theatre with a good sound system is hard to beat. I think live shows have the potential to be much cooler than the record, but the sound system has to be right. And our local haunts here in town where we played our first gigs are always really fun.

SJ: Recently I heard someone say (something to the effect…) that there was a new generation of dobro players on the scene and that it was only a matter of time before everyone would start to sound the same. What do you think of that? How do you see the role of the dobro evolving in acoustic music and music in general?

BC: That’s what would happen if everyone was ‘trying’ to sound a certain way, listening to the stifling laws of tradition instead of their own hearts. There’s a space that music is supposed to come from, and if it’s coming from there, it’s not possible for everyone to sound the same. Not like I’m some spiritual guru, but I know enough to know that that statement is totally missing the whole point. Honestly, it makes me sad to read this.

I think people are learning more about what can be done with the instrument. I think it’s a huge challenge to be as musically expressive as a person wants to be with a dobro, and takes more woodshedding to get to the point of open mind and heart musical freedom than pretty much any other instrument. But hopefully, with the direction of our heroes, we can all get a little closer.