SJ: I recently read a book called the Power of Habit which claims that 40% of what we do on a daily basis are the results of habits. What’s your perspective on the role of habits as it applies to playing the dobro? Can you share any specific examples?

JH: Habits are everything! What we endeavor to do when learning is to create habits through repetition and by building muscle memory. From there our hands and thoughts come together and create the music. Virtually nothing you’ve ever heard has been the result of a lightning bolt or a result of “on the spot” brilliance. So we need habits or muscle memory to channel our creativity in music. The problem arises from bad habits. The dobro is unique among bluegrass instruments in that you can pick it up and with virtually no technique at all you can make pretty pleasing sounds by just moving the bar along with the chords. Now you can do this with your pick on backwards on your pinky or your thumbpick on your pinky and your metal pick on your thumb. The point is you can do everything wrong on the dobro and still make it work to a certain level. To my knowledge you can’t play a fiddle, banjo, guitar or mandolin unless you tackle the rudimentary techniques. To my experience with many many students this is the main “bad Habit”. Players pick up the Dobro and with no one to guide them or emulate locally and begin to play. They then “Burn In” habits that create a ceiling which is virtually impossible to break through once they try to start emulating what they hear a records.

There are always several ways around the barn and one player to the next will have slight variations on how they accomplish what they set out to play. What is common to all good players is economy of motion and excellent left hand technique. Those would be the habits to “burn in”. I’m constantly looking for new pathways for my hands to travel, create a new “habits”. For me the “habits” that I carry with me as I explore are economy of motion and left hand technique. Anything explorable on the Dobro will flow from that.

SJ: Are there certain habits which are more important than others for someone who is just getting started on the instrument – perhaps right hand position, balancing out the use of the thumb and fingers, damping behind the bar, etc?

JH: They are all important for somebody that’s just getting started. For example, it’s pretty easy to learn to reposition your right hand away from the bridge. That’s not a very difficult change to make but it pays big dividends. For example, you could have the best technique and red hot licks but if you’re picking to close the bridge it’s all for nothing. Next would be learning to base your right hand picking around the thumb. I have seen hundreds and hundreds of students who have taught themselves and not learned to balance out their right hand by basing it around the thumb. The thumb is the strongest finger and if used in conjunction with the index and middle balances for a nice even distribution of the workload. If you think about it like a flatpicker uses a pick on the guitar most of the time the pick is going down and up. There are exceptions to this where after a long note flatpicker will use two down strokes. Well it’s the same on the dobro. The thumb would equate to a downstroke and either the index or the middle would equate to an upstroke. Dividing the workload of the right-hand in this way has a certain balance to it, just like the flow of the right-hand of Tony Rice, Sam Bush etc.. You could even see it in the bowing of a good fiddle player or the driver a locomotive wheel.

If you’re starting out or even been at it a while and can get a grip on those two things you will find yourself way ahead. Everything else of course going to need attention eventually and with practice most will get there. Welding these two techniques into your playing will go a long way, helping to smooth out your playing.

SJ: How do you help someone “unlearn” a bad habit?

JH: Basic answer is just to stop doing it. But I think the real answer is a little deeper. First thing in my mind is to demonstrate and have student totally understand how detrimental somebody’s habits can be to their playing. To undo anything as ingrained as a bad habit or any habit for that matter requires a lot of discipline. You need to totally remove it from your muscle memory and default way of going about things. That takes a lot of practice undoing. When we play music or improvise you’re traveling down well-worn pathways with our hands and heads. It took a lot of work to get those habits into our playing. Rooting out bad habits may be even more work so I am a big believer in dramatically demonstrating the upside to correcting a bad habit.

A bad habit will definitely show up in your playing and usually can be heard very easily. I’m very big on recommending my students record themselves and critically listen back. Hard to do but necessary, you want to be able to hear what other people are listening to when they hear you. I prefer to correct that before I leave the house. That being said mistakes happen everytime you play and the sooner you get used to that the happier you will be.

SJ: What about the habit of relying on tablature vs. training yourself to play something by ear? It seems to me that requesting tabs for different songs has become the default on the Reso Forums. And while I understand the attraction to tabs there’s a tendency for those who rely on them to neglect ear training which is one of the basic building blocks in becoming a good musician.

JH: As you know Rob I learned to play when there really wasn’t any tab out there. I had to use my ears, picking up the the needle on the record over and over. Slaving over a hot turntable.:)

So my answer about tab maybe a little bit skewed. I learned by critical listening and looking back I believe is the best way to learn. Having said that I am in the tab business. I do realize that most folks will not have the amount of time to invest as I did and do. Learning music has consumed my whole life and I wouldn’t change it for anything. For those out there that don’t have your whole life to invest there is tab and video’s. I do believe that with all the modern learning aids today a good percentage of one’s time should be invested in developing the ear. I have told many many many students that the ear is a muscle. The more you use it the stronger it gets and that is really is true in my experience. Even after 40 years of using my ears I hear and more layers to music and Dobro every day. It’s a very beautiful thing and I wouldn’t want anybody to miss out on the experience. I imagine everybody reading this is going to be a Dobro player, so folks do yourself a favor and pick something simple out and really listen to it. Do it a hundred times and email me in the morning.:)

SJ: What causes players to have difficulty improvising, even over the simplest chord changes? How does one break out of the “I can’t improvise” habit?

JH: From what I have experienced the difficulties arise from players not really knowing the scales or trying to play them in a difficult position. That brings up Catch-22 situation, if a player is not successful trying to use scales they tend not to practice them in yet tons of practice is the only way they can use them. Improvisation and creativity are acquired skills. You have to crash and burn 100 times for every successful attempt. Again in my experience for some reason players are afraid to make mistakes in music. If you think about anything you know how to do well you made a ton of mistakes learning it. Why would music or dobro playing be any different?

So I think the problem is twofold. You would need to know where the notes are on the fretboard without question, second nature. Then attempt to use them without fear, make mistakes and learn from them being prepared to accept new mistakes as you venture forward. In my workshops I always feature A lot of time on scales. I then grab a guitar and play rhythm while they play around in the scales. It never fails, they light up with a big grin as if to say ‘ I didn’t know I could do that”. And there you have it, learn the scales and put yourself out there. It only works if you do it, no shortcuts.

SJ: What causes players to get stuck in ruts when it comes to playing solos and how do you help someone break out of their comfort zone?

JH: For me breaking out of a rut involves learning small new bits. I find if I learned a very small lick or technique I’ll work it into something I already know it makes everything I know sound different. I love that . I get for tired of sounding like myself I think everybody does. A new lick, Position, rhythmic phrase or grouping of notes does the trick for me. And believe me it can be very small. I have a very small pocket of notes that I learned last night listening to Rob Ickes, I’m doing a concert tonight and I will be using it on every song. Goodbye rut!!!!!

SJ: It seems to me that a good portion on the instructional materials available approach the learning process from a “monkey see monkey do” teaching method. Yet, I know from experience that each student may learn in their own way and at their own pace. Can you share any observations from your teaching experiences about what constitutes effective learning and practice habits on the part of the student? Is there a difference between working hard and working smart when learning to play the dobro?

JH: There’s a huge difference between working hard and working smart. Just because you’re working hard on something doesn’t necessarily mean you’re working hard on the right things. I always encourage students to pick out things they know they’re going to need when they play in the immediate future. That’s one example of working smart. It’s hard work and very time-consuming to learn any instrument your resolve and patience will be tested. We all have that in limited quantities of each so for me it was always a matter of achieving real progress before my resolve gives out. I think it’s very smart to reach for things to learn that you will need to know the next couple times you play with the people you play with. If you have to take a solo on “Love Please Come Home” for example look for ways to creatively state the melody and make it sound good for the Dobro.It doesn’t have to be hot or hard. Check out options for soloing over the 7 flat chord which is common to many songs and occurs in “Love Come Home”. Look for ways to play over the 5 to 1 chord change which is also in that song and every song you’ll ever play. Check out rolls again which you can use to solo on this song and….almost every song you’ll ever play at a jam. To me that’s way smarter than learning some little known instrumental that is sure to be a jam buster.

As for effective learning and practice habits, I find from my experience that critical listening again comes up. When a student plays me something I know that they are not hearing it the way I hear it. So why not? The answer is I have had years and years of developing my ear to where I can hear things on a very very deep level. One easy way to start that journey for students is to learn to listen to yourself as you are practicing. Too many players practice licks over and over again and are not listening intensely as they practice. The more you tune out the world and zone in on your playing, the more you will hear every day.

When I am practicing I will jump out of my skin if somebody walks in the room and says hi. I am not aware that anybody entered the room. I wasn’t born like that I developed the focus I need a little bit at a time by really listening.

That focus will help you hear things on records and in other dobro players playing that you never dreamed where there. You’ll find that you can learn faster and sound better at the same time. At least that’s the way it’s worked for me and I’m still working on it.

Practice slowly and make sure each note has a place not just something you lump together to get to the next lick. Practice below your top range so you can put things in your muscle memory relaxed. The way you put it in your muscle memory is the way it will come out. Put it in tense and jerky it will always come out tense and jerky. Guaranteed. Listen to your tone. Record yourself OFTEN and listen to it OFTEN. Your favorite players have done exactly that.

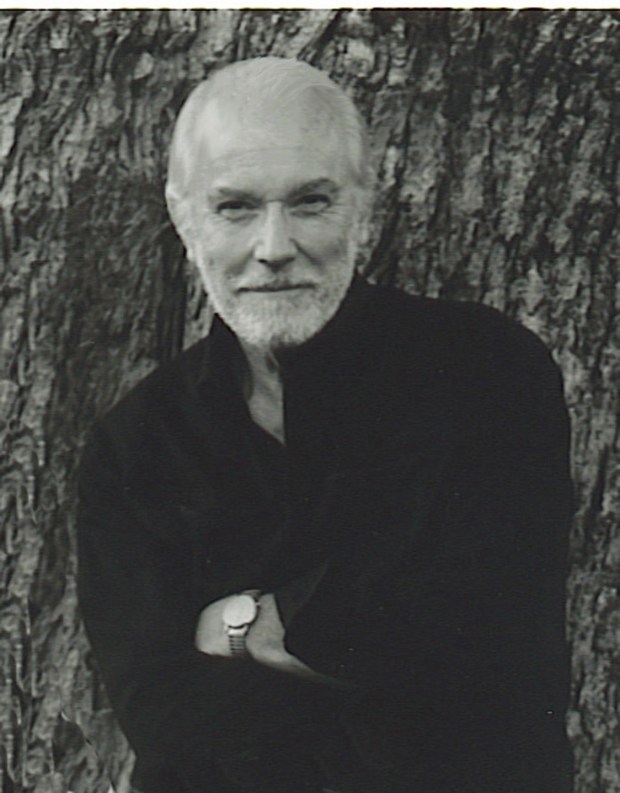

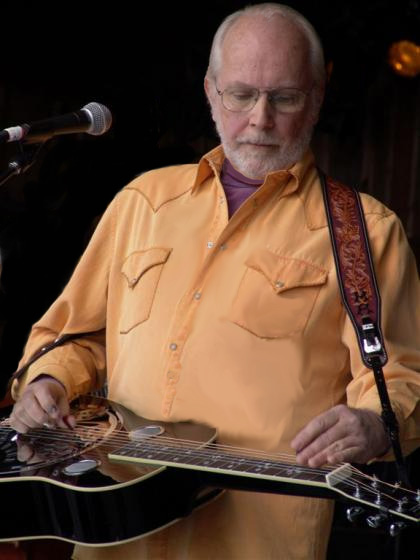

Jimmy Heffernan is a highly respected Nashville session player, sideman, and producer. He’s also a versatile multi-instrumentalist and a truly gifted dobro teacher. Visit Jimmy on the web at JimmyHeffernan.com