Originally published at http://www.robanderlik.com in 2009

SJ: I assume you grew up in Germany, correct? Where/when did you first hear or see a dobro? How did you get interested in playing one in the first place?

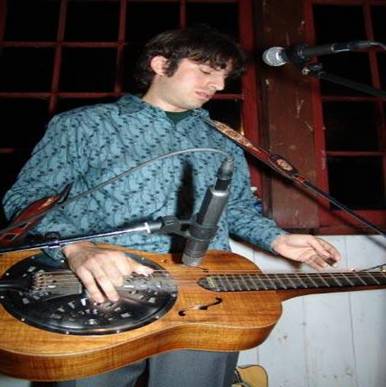

MG: This is absolutely correct. I grew up in Southern Germany. When I consciously listened to a dobro for the first time is hard to tell. In the seventies when I started playing the guitar and was listening to records by Eric Clapton, the Allman Brothers or various Blues artists, the sound of this instrument always amazed me – that was a long time before I even knew its name. Only after I came across a record by the Allman Brothers whose cover showed a dobro did I realize what one looked like. I studied that picture closely and soon decided that I would one day possess such an incredible instrument. In the year 1978 I achieved my goal. On a trip through the USA I bought my first dobro in New Orleans. It was a metal body dobro which at that time cost $ 400 – and was identical with the one on the cover of the Allman Brothers record. I felt perfectly happy then. At that time I had no idea that there were also squareneck dobros and naturally I had never heard of Bluegrass music. Such was the situation in Germany when I grew up.

But this changed two weeks later when my journey led me to San Francisco. At the turning point of a cable car I happened to see a Bluegrass band and one of the boys played a dobro lap style. This took me by surprise and made me feel really excited. That technique of playing, that sound and that kind of Bluegrass music in general filled me with enthusiasm. After a long conversation with that musician I had found out that those instruments were produced in Huntington Beach. I knew where Huntington Beach was because I had passed it two days earlier. If only I had had that information at the time!!! Nevertheless, I decided to change my plans and travelled right back to Huntington Beach in order to visit the dobro factory. The manager, Ron Lazar, was incredibly nice, showed me around and informed me about the whole range of dobro manufacturing. Apart from that he gave me the address of a German dealer selling dobros close to Munich. When I returned home, it didn’t take long until I possessed my first squareneck dobro.

SJ: Where do you trace your musical heritage from on the dobro? Who were your heroes when you were learning to play?

MG: It was definitely Mike Auldridge. At that time there were no records, manuals or workshops whatsoever for people wanting to learn this instrument. Not to mention teachers. Luckily the dealer in Munich not only sold the dobro to me but also a Stevens steel bar and two Auldridge records. That was all I had to start with. In the following time I continually listened to the sound of those two records and tried to imitate the tunes as well as I could. Today I am really happy about the fact that it was Mike Auldridge who has had a formative influence on me at this early stage. Mike plays incredibly clean and has an excellent sound. As time went by I tried to find musicians in the region with mutual interests and found quite a few in Stuttgart. They were representatives of all kinds of styles like Irish Folk, Blues and there were even Bluegrass musicians, who made me acquainted with Stacy Phillips’ manual ‘The Dobro Book’. This really helped me a lot to learn more about playing techniques. Through those musicians I was able to obtain first-rate recordings and when I listened to Jerry Douglas for the first time it was clear that no other instrument would ever fascinate me as much as the dobro. Mike Auldridge, Stacy Phillips and Jerry Douglas had the greatest influence on me during my early years with this instrument.

SJ: How did you learn to play? Were there any special practice techniques or tools that you found especially helpful to advancing your playing skills?

MG: In the first half year I played without fingerpicks. That was easy for me, because on the guitar I was able to play the ragtime finger-picking style. It seemed logical to me to simply transfer this technique onto the dobro. I quickly realized, however, that playing the dobro this way, you don’t have a chance to get heard among the other instruments in a jam, for example. The sound is bad, there is hardly volume and your fingers ache. So, thumbpicks and fingerpicks became essential. This meant a complete change and I felt like an absolute beginner once more. At least I could profit from one ragtime technique: dampening the strings with the fingers of the right hand didn’t cause me any problems. If you don’t have anybody to guide you in learning an instrument you can’t help getting things wrong and later it is extremely difficult to get rid of those wrong habits. For example, after having used the wrong technique for years, I only learned on a later journey to the US how to chop properly. Naturally I had to practise very hard to set things straight. One specific technique which I have studied a great deal is using string pulls. In fact they characterize my personal style and I like using them a lot. I think that this way you show a certain affinity to the pedal steel guitar and this is what I like.

SJ: Can you give us any examples into how you approach the general concept of creativity on the dobro? For example – do you write your own tunes? How do you find something “new” to play in the case where you are playing a familiar tune? Just curious, have you ever transposed any traditional German folk music for the dobro?

MG: I think that the creativity of a musician has, among other things, something to do with being open for all different styles of music. It’s clear that there’s a lot that you don’t like, and you forget that pretty quickly. There’s nothing wrong with that. The things you do like though are automatically stored in your head – at least that’s the way it is with me. It could be a melody, a harmony, a rhythm, a mood produced by a song, or even just a simple lick. It doesn’t matter, but whatever you like, you remember it in some form or another. The more music you listen to, the more these elements accumulate, and as time goes by a basis for your musical preferences develops. Now it does depend on how much imagination, fun, and boldness a musician has, in employing his gathered impressions and putting these elements together, mixing them, experimenting with them in whatever form they may be. In my case it’s not absolutely necessary to have an instrument on hand to do this. I, personally, have my best ideas while driving. I listen to something on the radio and suddenly I have an idea. Then I have to turn off the radio right away and start developing my idea. I can genuinely hear the tones and harmonies I am imagining. If I like what I hear, I don’t forget it in the course of the day, and in the evening when I have my peace and quiet, I sit down and work the chords and melody out on the guitar.

It doesn’t really matter if that song lends itself to the Dobro or not. If so, all the better; if not, then it can be arranged for another instrument. This is how the basis of a song or instrumental number comes into being. Sometimes an idea comes while I’m just playing. I play some song on the Dobro and at a chord change I accidentally play at the wrong fret. It can be that I then say, “Hey, that actually sounds great!” and I’m suddenly hot on the trail of another idea, which I may be able to use. Sometimes, when no one’s listening, I go crazy on the Dobro and make a hellish noise, and play, very honestly, intentionally wrong. I just do this for my own fun. As absurd as this may sound, this is where I get my best songs. Jamming with other musicians is also very inspirational. It spontaneously produces an unbelievable potential for ideas. It’s just a shame that you can’t hold on to your idea and develop it further because the jam keeps on going. By the end you’ve forgotten everything. I always hope that at least the inspiration has been stored somewhere in my memory. It’s difficult to explain how creativity and composing really work. It certainly has something to do with inspiration, which in my case can take on the most diverse forms. What I know for certain is that I cannot just do it at will. I could never say that tomorrow afternoon between three and six pm I’m going to write a song. In answer to the last part of the question, I have to say that I recorded a German lullaby, composed by Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897). It’s called „Guten Abend Gute Nacht“ (trans. Good Evening Good Night) and can be heard as a video clip on my home page. I’ve also arranged a folk song called “Das Loch in der Banane”(trans. Hole in the Banana) from the German guitarist Klaus Weiland and put it to music on “Heart of Steel”.

SJ: Tell us about the band you play with: what kinds of ensembles do you play with? Do you do any “solo” Dobro gigs?

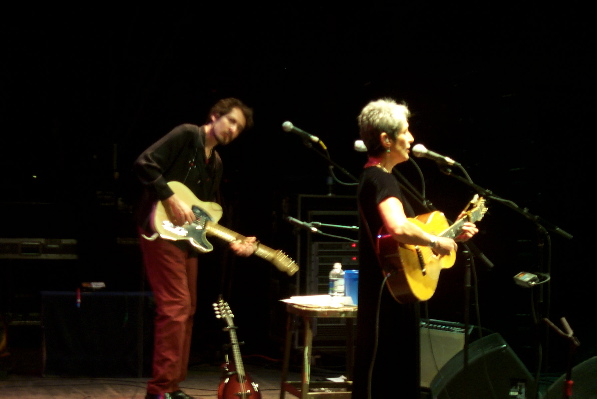

MG: No, I don`t do any solo Dobro gigs. But there are two bands that I ́ve been playing with, for many years now. The musicians got together because Bluegrass Music was their common interest. We do about 25 gigs a year. Unfortunately we don`t have the time to practice together a lot but we have a big repertoire of songs and instrumentals that we can lay back on. The Phoenix-Stringband and was founded in 1991. These guys had been picking together for quite a while and needed a bass player. So I started playing bass in this band. It was in 1998 when we decided to include the dobro in our repertoire for an entire set. We do the dobro set without the banjo so another member has got the chance to play the bass. The Phoenix-Stringband plays different kind of styles like Swing, Jazz, Bluegrass, Folk and even does arrangements of Pop and Rock songs in order to present a variety show to the audience. It was in 1997, when I joined the second band. The Four Potatoes is a strictly Old Time Music band where I also play the bass. Even if historically the Dobro is too young for this style of music, we use it for a couple of songs.

SJ: Your musical interests seem to range well beyond bluegrass, as evidenced on your stellar solo c.d. – The Heart of Steel. How did Heart of Steel come together? Are these the same musicians you play with on a regular basis? Where can people purchase your c.d.?

MG: If a musician makes music for a long period of time and focus interest to a special kind of instrument, there naturally comes the wish some day to show what he learned. I think this is an honest and natural need of every musician and has nothing to do with an image complex.

( Profilierungssucht ) I recorded the Heart of Steel because I had a lot of own composition material, that I wanted to keep for myself – in the first place. To me a CD is a document that shows the level of improvement, at the particular time it was recorded . This is important to me, because I want to control the progress in my development. The Heart of Steel is my first solo CD. Only local musicians were involved in this project. If you are interested in buying a copy, you can order it via PayPal on my home page http://www.martingross.com. (just click on shop in the menu). Betty Wheeler has a contingent of CD ́s in stock, and does the US shipping for me. The videos on your website are fantastic! I thought the quality of the images, the camera angle and of course, your playing is first rate. Are the videos available in a DVD format to folks here in the U.S.? Of course it makes me very happy every time I hear that people are enjoying the Videos on my home page. If you’ve already seen the Videos, you’ve probably noticed that they’re not perfectly synchronized. That’s because there’s two separate steps involved, the first one being the Audio track, and then the Video, which causes a slight delay. If anyone’s interested in a DVD, I’m open for suggestions and feel free to contact me any time. I’ve never really thought about selling any because there’s no Tablature to go along with them. That’s quite the assortment of resonator guitars on your website! It’s just a hunch on my part, but I suspect if I owned 10 guitars I would eventually find one that I liked the best and play it most of the time. Is that true for you?

SJ: Please tell us about the different guitars you own; did you go through any kind of consumer rationalization process before making each purchase?

MG: Yes, I do have an instrument that I favor the most and use it for most of my gigs. I have 5 Dobros and each and every one of them means something special to me. So much so, that I couldn’t even imagine ever actually selling one of them. As mentioned before, my first Dobro, bought in New Orleans in 1978 for $400,- is a round necked Metal Body Guitar. In 1979 I bought my first square neck in Munich. Unfortunately, I don’t have this one anymore. I can’t even remember exactly what model or make it was. I bought my first real quality square neck from Rudy Jones in 1982. I had the opportunity to try out a number of different models at his shop in Waynette Oklahoma and told him exactly what I was looking for. Then he built me a custom Dobro just the way I wanted it, I chose to go with Mahogany. The Reed Guitar came about through a friend of mine. He had it built for himself and shortly before the delivery date heard the news that Bob Reed’s shop had burned down. The Dobro, fortunately, was not damaged in the fire. At any rate, this is the very last Dobro that Bob Reed built. In the winter of 2003 I stumbled across the Sheerhorn on eBay. It was custom made for a person in Calif. in 1991 out of Maple. It’s the first one Tim ever made with F-Holes and has the serial No.26. My latest acquisition is from a Luthier here in Stuttgart named Siegfried Dessl, built to my specifications. The body is made of two different types of mahogany. The top is made out of Tobasco, with F-Holes, and the back and sides are out of Sapele.

SJ: You’ve been playing for awhile now, correct? Are there any techniques or goals that remain elusive for you? What kinds of things motivate you to tackle a new tune or technique?

MG: I got my first square neck in 1979 and that’s when I started to learn how to play. But between 1988 and 1998 barely played at all, as a result of focusing all my time and energy on Studio Recordings and Song Writing. At some point we decided to bring the Dobro back into the Band and that’s when I re-discovered my long lost love for the instrument. There’s so many things I’m interested in doing, and goals I’ve set for myself as a Musician. One of these is to really learn the right way to play my rhythm chops. I also feel I need to work on my timing. I would love to go to a Bluegrass Festival or two in America and attend some of the Workshops and get the opportunity to meet the whole Dobro Family. A second CD is also way up there on my list. The time and energy I spend striving to achieve all my personal goals and making my dreams come true is a constant source of motivation for me, and is a very important factor in my own musical development.

SJ: I was fascinated to see on your website that you had designed your own dobro capo. What inspired you to do that in the first place? How does your capo differ from other dobro capos available in the marketplace?

MG: Where did the motivation for designing my own Capo come from? You know the old saying, “Necessity is the Mother of Invention”. Well, the fact is, I needed a Capo and I just didn’t have one. I tried fooling around with regular Guitar Capos that I’d modified for the Dobro, but wasn’t really satisfied with any of the results, so I decided design one myself. The first few prototypes were very promising and today I’m very happy with the Capo just the way it is. The advantages my Capo over the standard Capos are: The Capo is fairly massive and has a lot of substance, which constitutes in a very strong and solid tone.

- Fast and easy to put on and take off

- Always in tune while capoed

- No Capo movement while playing, because it rests on the neck

- More freedom for the pinky finger left hand

SJ: Thanks so much for taking the time to share your story with us. Do you have any closing thoughts you would like to share?

MG: My pleasure Rob! I consider it an honor to be included in your Featured Artist series and want to thank you for giving me the opportunity to be a part of it all. I’d also like to thank you for all the work you’ve put into your Homepage, which is a great source of information and motivation for all of us.