Originally published at http://www.robanderlik.com in 2008

SJ: Tell us about your musical chronology: where did you grow up, how did you get started playing music and when did you start playing resonator guitar?

DH: I grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts, which is a suburb a little Northwest of Boston. My father plays piano, and so did my grandfather, so I grew up hearing lots of standards and older pop songs as well as the Bach inventions and Chopin and Beethoven pieces my dad liked to play. My first instrument was the violin, because you could start on a stringed instrument a year earlier than the brass and woodwinds and I was just dying to start playing something; I played violin all the way through high school, but as soon as I got a guitar, it was really all over for the violin. I went to a summer camp in New Hampshire for a couple of years in junior high where there was a lot of old-timey and folk music and I learned a little clawhammer banjo; when I got back from camp and wanted to continue with it, my parents borrowed a guitar from the neighbors instead and signed me up for group lessons with a local teacher who turned out to be Lucille Magliozzi, the sister of the Car Talk guys. So that was my introduction to bluegrass – she taught us flatpicking and fingerpicking, and showed us a few fiddle tunes as well, which was very weird considering that everyone around me was into Kiss and Peter Frampton that year. At exactly the same time, my sister got all these Beatles records for her birthday, and sat me down to check them out, so that was my world: George Harrison and “The Girl I Left Behind Me.” In high school, I found out about B.B. King and John Renbourn, and also, I suppose, Preston Reed and the Allman Brothers, so I was into both fingerstyle guitar and anything having to do with the blues by the time I got to college.

My freshman year at Wesleyan University, I was studying harmony and counterpoint and pretending to understand Thucydides when I met Steadman Hinckley, who was a senior, a Russian major, and the rehearsal hall monitor on the same night I had my classical guitar lessons. He played slide guitar, and used to hang out and practise on an old Guild dreadnaught in between signing people in and out of the building. So he showed me open D tuning and how to play Duane Allman licks over a steady thumb bass, and we would go into the stairwell of this three-story cinderblock building and hammer away at a blues in D for forty-five minutes at a time with all this fabulous natural reverb bouncing off the walls and the ceiling.

When I got out school I moved to New York, and I thought that I wanted to be a jazz guitarist, which is what I’d ended up studying in school, and I had a half a dozen lessons with Emily Remler, who was obsessed with Wes Montgomery but also made some lovely records of her own (Transitions is the one to get, for my money). Slide guitar was just this blowoff thing I did for fun, until a couple of friends took me to see Nancy Griffith at the Bottom Line; I was probably 23 or 24 and there was this guy in her band playing Dobro, pedal steel, fiddle and accordian. I thought, “I have to do that. And I have to do it now.” I went into Matt Umanov Guitars on Bleecker Street the next day and asked if they knew anybody who gave Dobro lessons; someone fished around in a drawer beneath the cash register and pulled out a business card. “Fats Kaplin does, give him a call.”

So I called the number they gave me and explained that I didn’t actually own a Dobro, but I wanted to learn to play; could I maybe come over for a lesson anyway and just play his and check it out? He said I could, so I went to this apartment building in the Village and went up to the eleventh floor; as I was coming down the hall the door opened and someone stuck their head out, and it was the guy, the same musician I’d seen with Nancy Griffith. I’d had no idea he lived in New York. He gave me about a two-hour lesson that day, showing me how to use the picks and the bar and how the high-G tuning worked. He told me to get some Flatt and Scruggs records with Josh Graves and played me a bunch of other things as well, and taught me his arrangement of “Grey Eagle.” He gave me a set of his fingerpicks, which were already bent into shape, and I went out and got a nut adapter for my acoustic guitar and a copy of Stacy Phillips’ The Dobro Book and started practising my slants and trying to figure out stuff off of records. I had a couple more lessons with Fats and when I’d been playing for a few months I went into the Music Emporium in Cambridge and found a 1930s Regal that had had the neck replaced by John Monteleone, and that was that. It had a really small body and a spruce top and sounded amazing; that was my main guitar for several years, and I still have it. I actually got to take some lessons with Stacy, too; I made him show me the basic Josh Graves open-position stuff and he really helped me understand how hammerons and pulloffs actually work.

SJ: How many instruments do you play? What do you consider to be your main instrument?

DH: I play acoustic and electric guitar, dobro and pedal steel, although I’ve hardly played steel at all since I left New York in 2000. I can also play just enough mandolin to squeak by in the studio, but that doesn’t count. I guess I consider myself a guitar player; I remember a Mike Auldridge interview in which they asked, “why do you keep calling them [meaning his Guersneys and Beards] guitars?” To which he replied, “Because it is a guitar, it’s a steel guitar.” and I suppose I think of it the same way – it’s a kind of guitar, so I’m basically a guitar player. But I do feel like I can express myself the most directly and emotionally when I’m playing some kind of slide instrument, whether it’s bottleneck guitar, lap-style resophonic guitar, pedal steel, or whatever.

SJ: Do you find one technique easier than the other? Do you have a preference for one vs. the other?

DH: I became a real snot about bottleneck guitar when I started playing lap-style: “Why would you even bother? You can’t slant, you can’t do hammerons and pulloffs, and you can’t get a clean sound,” blah, blah, blah. But you can hammeron and pulloff – just check out Ry Cooder – and all that scrape and clang is part of what makes bottleneck slide so excellent. I’ve come back around on slide guitar; I like being able to draw from both sides of the family. When I’m playing lap-style, I’ll steal anything that isn’t nailed down from the slide guitar guys I love – all those early Muddy Waters licks are just sitting there in open G tuning, since that’s what he was using then, and I still use everything I learned from Duane Allman about phrasing and right-hand technique in the closed position. And I’m sure I go for certain things now in open position on the guitar that are totally Dobroistic, if that’s a word.

SJ: How long were you playing before you started playing in a band? Tell us about the bands you’ve played in. What kind of influence have other musicians that you have played with in bands had on own your own development as a musician?

DH: When I started playing the Dobro I was already playing guitar in Freedy Johnston’s band, so when I’d owned my Regal for about three months and been playing for six, we rehearsed some tunes for an acoustic set and played a gig somewhere in New York. I still remember looking down at my hands somewhere around the third tune and having this flash of, “whoa, what’s this all about?” Then everything went back to normal. I think I even used a crazy halfway-C6 tuning that I must have made up, to get a Western Swing sound on a song called “Truck Stop,” tuning down the top two strings to A and C. I also did my first sessions on Dobro with Freedy, playing on two songs on his first record, The Trouble Tree, in regular high-G tuning. I was probably about 25.

The whole time I was living in New York, I really wanted to play in a bluegrass band, sing harmony and play the Dobro, but it was hard to find a situation like that, so I played with singer-songwriters instead. I played on a lot of Fast Folk records, and toured with Jack Hardy, who’s been running a Monday night songwriter’s meeting on Houston Street in Manhattan since the late Cretaceous period. We went to Italy and I kept having to use my fifty words of Italian to explain about the Dopyera brothers in between large mouthfuls of gnocchi. I also worked with a songwriter named Jeff Tareila. Since it was just the two of us and he really loved the instrument, I got to take a zillion solos and play for as long as I wanted, especially if we wound up on some gig where we realized nobody was listening anyway. Playing with songwriters meant learning to negotiate a lot of different kinds of chord progressions and grooves, which I really liked. At the same time, I was going through a similar process on the pedal steel, which I started two years after the Dobro, and in pretty much the same way – going over to Fats’ place to check out his Emmons single-neck, listening to the records he gave me and learning about technique in a hands-on way.

SJ: One of my friends describes the history of the dobro and coming in two main eras: Josh Graves and Jerry Douglas. Obviously that is an oversimplification, because it leaves out the contributions of so many great players – Oswald, Auldridge, etc, etc, but perhaps there is some truth there. How do you see the history of the instrument and who do you trace your musical lineage to?

DH: I’ve always seen it in three eras. To me, Josh Graves, Mike Auldridge and Jerry Douglas are like the the Abraham, Isaac and Joseph of the instrument. I may actually be the last Dobro player in captivity to have heard Mike Auldridge before hearing Jerry Douglas. I saw the Seldom Scene in at the Bottom Line in New York – the same place I saw Nancy Griffiths, in fact – just a year or two before I started playing, although for whatever reason it didn’t really have the same shazam! effect on me that Fats did with Nancy. If must have gotten me thinking, though, in some way. I still remember the way it looked as Auldridge played; the effortless way he would tilt the bar in his hand to slide into a note on the high string.

At any rate, that first year I was playing, I basically had a copy of the Seldom Scene’s Act Four and Flatt and Scruggs’ Blue Ridge Cabin Home. The Josh stuff I could kind of pick out just listening, but I had to go measure by measure, writing everything down, to get Auldridge’s solos on “Daddy Was a Railroad Man” and “Tennessee Blues.” I think the first Jerry Douglas I heard was on Ricky Skaggs’ Highways and Heartaches, which I got for twenty-five cents at a used bookstore by the F train in my neighborhood because it had Jerry on two cuts. I learned about playing in the key of D in open position from slowing down stuff of Jerry’s, probably on Tony Rice’s Manzanita – there’s also a bluesy chromatic lick in closed position on one of those songs that I still use some version of.

But I think the combination of starting with Auldridge and Josh, coming from a slide guitar background, and being a guitar player as well, all helped me not necessarily come straight out of Jerry. Besides, I was never all that fast on the guitar to begin with, so I knew those wicked tempos he does just weren’t going to happen. I loved Douglas’ whole lyrical side, and have listened to Skip, Hop and Wobblemore times than I can count, but when I started doing session work in New York I was always really pleased people told me I didn’t sound like Jerry Douglas.

SJ: On the behalf of the reso-community a BIG thank you for including so many great articles in Acoustic Guitar magazine featuring square-neck resonator guitar and today’s greatest players. How do you see the evolution of our beloved instrument – past, present and future? For example, will there ever be a day when we the general public will see the dobro as being associated with anything beyond roots music – bluegrass, country, swing, folk, etc?

DH: It seems to be already happening, doesn’t it? At least, the family’s getting that kind of respect now: look at Ben Harper, Kelly Joe Phelps, and Robert Randolph. Jerry Douglas has been profiled in the New York Times Magazine. This is always the question in the pedal steel community, too: “Where is our Jimi Hendrix, the guy who’s going to make the instrument a pop-music phenomenon that the kids want to pick up?” I don’t know about associations beyond roots music, but pop music tends to go through waves of rootsiness itself, and this time around it seems to have picked up its share of reso-baggage along the way.

SJ: How did you come to be so well-known as a teacher?

DH: I don’t really know. I started teaching at the National Guitar Workshop early on, which led to writing my first book, Beginning Blues Guitar, and that in turn helped me get involved writing lessons and stories for Guitar Player and Acoustic Guitar. I like explaining things – it’s a family trait, or a family flaw, depending on how much of your time you’ve spent around one of us. I didn’t really set out to be a teacher; it just kind of happened along the way. It was cooler than having a real job.

SJ: In 1998 you published The Dobro Workbook, which includes tablature/c.d. Can you give us an overview of your book/method? Where can our readers purchase a copy?

DH: It’s basically a book on how to build your own vocabulary of bluegrass licks and phrases and put them together into solos. I use fiddle tunes for the examples but everything is meant to be applied to any kind of song, really. I focus on developing the whole hammeron/pulloff approach in open position in the keys of G and D, go on to look at the “melodic style” of playing up the neck while still incorporatingn open strings, and talk along the way about how to deal with the other chords that come up in those keys so that you have some strategies for playing over, say, an E7 in the middle of a tune in G.

It sounds contradictory at first, but the point of the book is to teach you how to practise improvising – what are the things you can learn and get good at that will help you improvise a break on a bluegrass tune? It’s basically a lot of the things I practised after Stacy showed me the basic Josh Graves moves, plus some other things that I should be taking the time to practise more myself. In another month or so you’ll be able to buy it from my web site along with my other instructional stuff and my CDs, but it’s published by Hal Leonard, so you can theoretically find it in stores. I know for sure that it’s available on the Elderly Instruments website.

SJ: Is it necessary to understand music theory to become a good dobro player?

DH: Of course not, but it sure helps if you want to play over anything out of the ordinary, or find your own licks and chord voicings. And if you want to get into lap steel tunings or pedal steel, I can’t imagine flying blind. I’ve known people who do, who loved the instrument and had really good ears, and it just went so much slower than it had to for them.

SJ: What can aspiring dobro players do to speed up the learning process? Why do some people advance so quickly why others are still playing at the same level for years and years?

DH: I think a lot of it has to do with how you practise. I’ve never been one of those hours-on-end practisers; my program those first few years was to spend a half an hour a day actually practising the Dobro. Sometimes I spent more time, and I might work for a similar amount of time on another instrument, but that was my deal with myself. And that half hour was really focused: ten minutes on left hand technique, ten minutes on right hand technique, ten minutes on learning a new song or solo. If you know exactly what it is you’re trying to get done, that short amount of focused time can really mean a lot if you hit it every day, or most days. Plus, it keeps you hungry for more, and you don’t build up any resentment towards practising or the instrument. You look forward to those thirty minutes.

SJ: What are you up to these days, musically speaking? Tell us about the bands and musicians you are playing with. Do you have any upcoming shows or events that you can tell us about?

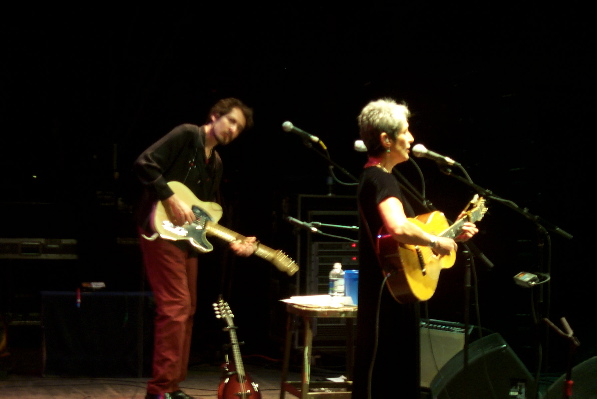

DH: I’m finally in an honest-to-God bluegrass band, the Grassy Knoll Boys, based here in Austin, Texas. We play on just two area mikes, and I get to sing three-part harmony, do a some lead singing, write and arrange some of the tunes, and play gobs of Dobro. I’m really digging being in a band after all the sideman work I’ve done. Everyone plays and sings great, and I’m particularly proud of our repertoire, which I think is pretty imaginative and still sounds like bluegrass. We’ve starting hitting some festivals, like Grey Fox in upstate New York and the Kerrville Folk Festival here in Texas, and are theoretically making our next record sometime this spring.

I also play some solo gigs from time to time, and appear once in a blue moon with my acoustic blues band Beaumont Lagrange; we have a couple of horn players and I play a lot of National.

SJ: Tell us about your c.d.’s – King of the Brooklyn Delta and Indigo Rose. Do you have any plans to release a new c.d. in the future?

DH: Those are my “pop records,” both recorded with my band at the time and both featuring my singing, writing and guitar playing, though each includes one Dobro instrumental and a fair amount of slide guitar. A few years ago, I released a five-song EP called “Barrelhouse Guitar” that was just guitar and vocals, and I’ve just finished up an all-instrumental solo guitar record called “David Hamburger Plays Blues, Ballads and a Pop Song,” which will be available on my web site soon. If someone wants to hear me play Dobro, the best thing to do is get the Grassy Knoll Boys record (at genuinerecordingsaustintexas.com). I’m also right in the middle of producing Michael Fracasso’s new record here in Austin, and I’m playing some slide guitar and pedal steel on that.

SJ: I hear that Austin, Texas is a great music town…how would you describe the local music scene there? Are most of your gigs local? Do you play outside of Austin quite a bit?

DH: The Grassy Knoll Boys have a weekly gig at Jovita’s in South Austin, and I’m about to start a weekly solo gig at Flipnotics, which is a cool little room I’m really looking forward to playing in. With the blurgrass band, we’re starting to create a regional circuit for ourselves; we get to Houston and San Antonio and Fort Worth every few months, and recently crossed the state line into Oklahoma to play at the Blue Door, which was a blast. Fortunately, after all that time driving, we’re still speaking to one another. It helps if you stop regularly for pop-tarts, preferably blueberry or strawberry. That really takes the edge off, especially between Austin and Dallas, which can be one bleak-ass strip of interstate.

SJ: Who are your favorite musicians to play with? Do you have preference for playing a certain genre of music on the dobro, say with a bluegrass band or swing band, etc.?

DH: Honestly, I like getting to take a flyer on anything left of center, to see if it’s possible – and in some ways, the less preparation the better, as long as it’s not in front of a jillion people, which hasn’t happened yet anyway. Either that, or just straight ahead, “whoa-this-is-fast bluegrass,” for sort of the same reason – that same sense of not knowing whether it can quite be done or not until you do it. Usually both situations make me realize that I need to go home and practise. Just thinking about this makes me think I should go and practise, actually.

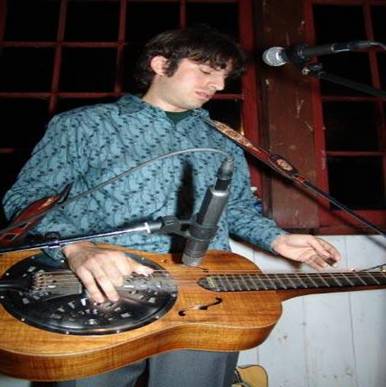

SJ: Tell us about your gear: what kind of resonator, Weissenborn’s or lap steels do you own?

DH: Besides the Regal, I have a 1996 Gibson/OMI 27-Deluxe Dobro, a 1939 Gibson EH-150 that I rarely play, a 1930s National Trojan, a relatively new National Reso-Phonic Estralita Deluxe, and a 1970s Emmons “push-pull” single-neck pedal steel.

SJ: What does your live dobro rig consist of? Any comments on getting a good “live” sound on dobro?

DH: The ’96 27-Deluxe is my main instrument for both onstage and in the studio. We use just two area microphones onstage with the Grassy Knoll Boys, Audio-Technica 4033s. It works most of the time. If we play someplace noisy, I have a Macintyre pickup under the coverplate and I just plug into that and go. The main thing I can say about playing on microphones is that it helps to be able to pick just as hard as possible. But it is really fun doing the choreography around the mike.

SJ: Any closing comments or words of wisdom for aspiring players?

DH: I once asked Gatemouth Brown when you should start working on having your own style, and without batting an eye he said, “as soon as you’ve got the basics down.” Now, what it means to have “the basics down” is kind of open ended, and of course one really good way to learn is to figure out how the musicians you love are making the sounds you want to be able to make on the instrument. But how is only half of the equation; the other half is why. You can never own someone else’s why, you have to come up with your own. If you just learn to play like other people, you’ll always only have half the picture. What do you want to play? What do you think it should sound like? What’s yourpersonality, and how is it going to come out on the instrument? Once you start to get a handle on that, you’ll have something all your own, and that’s the bedrock every musician ultimately needs to find.